What about Black unemployment? We did not start tracking this until 1972. Since then, however, the data shows that while Black unemployment is twice as high as white unemployment, the two rise and fall together with the economy. (One exception is that the recessions that affect white Americans usually affect Black Americans much more.)

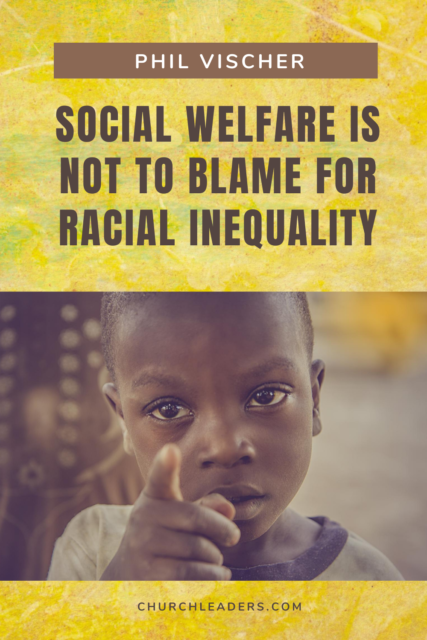

Nevertheless, this data is enough to show that “the notion that inner city African American communities were doing just fine until the government came along and messed everything up is entirely false.” Said Vischer, “There is no evidence in unemployment data that the welfare policies of the 1960s are responsible for higher Black unemployment today.”

In fact, when Johnson launched his War on Poverty, it was primarily to benefit poor white people in rural areas. That is interesting because today people often associate welfare with Black families in urban areas. Why is that?

To answer this question, one researcher studied 40 years (1950-1990) of back issues of three major magazines—TIME, Newsweek, and U.S. New and World Report—cataloguing every article about poverty. In each one, the researcher looked at whether the accompanying images depicted white people or Black people.

He found that before 1960, more than 80 percent of these articles pictured rural white families. In 1964, the majority (75 percent) of the pictures were still of white families. But in 1965, half of the pictures were of Black families. In 1967, 70 percent of the images portrayed Black people.

What transpired in that short time frame? One change was that civil rights activists were focusing on economic justice, and there was “a burst of news stories accompanied by pictures of impoverished Black Americans.” Another change was that protests and riots drew attention to the inner cities, while another was that the public started viewing Johnson’s policies less positively. So just as people started viewing his welfare programs in a negative light, the media also started associating poverty with the Black community.

African Americans currently make up less than 30 percent of those below the poverty line and receive a third of all government spending. White people and Latinos make up the other 70 percent. Yet when we think of welfare, we think of Black families because we’ve been fed those images so often.

“Here’s the sad reality of lingering racism in America,” said Vischer. “The more we think of poverty as a Black problem, the less we want to help…As Christians, called time and time again in Scripture to care for the poor, this is nothing less than tragic.”

Why Apologize for Other People’s Actions?

The third question Phil Vischer briefly tackled was essentially, “Why should white people apologize for the sins of their ancestors?” Put another way, why should individuals take responsibility for something they have never personally done? Vischer pointed out that the Bible talks about individual sin and repentance and societal sin and repentance. He cited Daniel 9 and Nehemiah 1 as examples of the latter. “We don’t like the idea of taking responsibility for sins we didn’t personally commit,” he said. “It isn’t very American. But it is very biblical.”

A related question some ask is, “What about the gospel? Don’t they need Jesus?” People certainly need the gospel, said Vischer, but before we simply assume that the struggles in the Black community are a result of a lack of the gospel, we should look at the data. And the data shows that Black Americans are more likely than white Americans to believe in God, say faith is important, read the Bible, pray every day, and have biblically sound theology. “In other words,” said Vischer, “if we’re looking for the most devoutly Christian group in America, that group isn’t white.”

The last question Vischer addressed was, “What can we do about such a huge problem?” While he admitted, “The problem does seem too big to solve,” Vischer also believes that there are some solutions that have been shown to work. He believes we should support access to free preschool, should work to balance funding between wealthy and poor school districts, and support efforts to train more African American teachers, mentors, and role models. Just as Nehemiah used his position of influence to make a difference, we need to do the same—not seeing ourselves as saviors, but as allies.

“The impact of historic racism still echoes in America, harming millions of lives,” said Vischer. “It is a problem. Let’s make it our problem, and let’s do something about it.”