“This is the greatest threat to the gospel in 100 years. It’s the new social gospel,” he explained, referring to progressive Christians’ call in the early 1900s to live among and improve the lives of the urban poor, which evangelicals of the time rejected.

Anthea Butler, a University of Pennsylvania religion scholar and author of “White Evangelical Racism,” said white evangelical leaders have long faced a dilemma when it comes to race: They want to bring people of all sorts to the church without disrupting the status quo outside the church. The legendary evangelist Billy Graham desegregated his crusades during the civil rights era of the 1950s and ’60s, Butler said, while also claiming that “extremists are going too fast.” Jesus, he said, would make racism “obsolete.”

“On the one hand, evangelicals wanted souls to be saved,” Butler writes in her book. “On the other, they wanted everyone to stay in their places.”

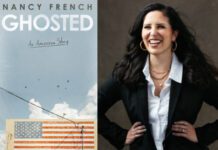

Anthea Butler. Courtesy photo

In an interview with RNS, Butler said those two goals are no longer compatible. Evangelicals, threatened by the country’s changing demographics, are fearful of becoming a minority in their own big tent if they pursue their historic aim to spread Christianity. The racial reckoning in the wake of Floyd’s death at the hands of Minneapolis police, meanwhile, has undermined the myths that sustained their power, she said, leading to pushback against calls for racial justice.

“They believe it is an existential threat to their nostalgia about America,” Butler said.

White evangelicals’ fear of being overtaken by other groups makes their claims of colorblindness hollow, said Butler. While Strachan and other anti-woke voices often point to the legacy of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., saying they want to judge people by “the content of their character” — not the color of their skin — they also reprise civil rights era claims that calls for racial justice are a disguised socialist plot.

“It’s the same arguments recycled in a new form,” Butler said.

But you don’t have to be white to mistrust wokeness.

James Pittman, pastor of the multiethnic New Hope Community Church in the Chicago suburb of Palatine, Illinois, has both theological and pragmatic concerns about CRT. Much like Strachan, Pittman, who is Black and conservative, argues that CRT assigns blame and guilt based on people’s ancestry or skin color — not on their actions, something that he says the Bible does not do.

But Pittman also worries that discussions about CRT and systemic racism overshadow other systemic problems in American culture — in particular, education inequality. He’s a critic of the Chicago school system, one of the nation’s largest, where Black students on the city’s south and west sides have often struggled.

“These kids are stuck in a machine,” Pittman said. “They keep putting kids in failing schools.”

Pittman, a graduate of Howard University and Trinity International University, pointed to the impact that education had on his own life. A New Orleans native, he attended St. Augustine High School, a Catholic-run predominantly Black preparatory school there for young men. That school gave him a great education and a sense of pride in who he is.

“The culture was, I’m going to teach you to read and write and to not play second fiddle to anyone,” he said. “It’s more than ABCs and 123s — it is a reaffirming of who you are and not to look at the color of your skin as a negative.”

He chafes at the idea that white supremacy could hold him down.

“I never believed in white supremacy,” he said. “I never thought that I was inferior because I am Black.”