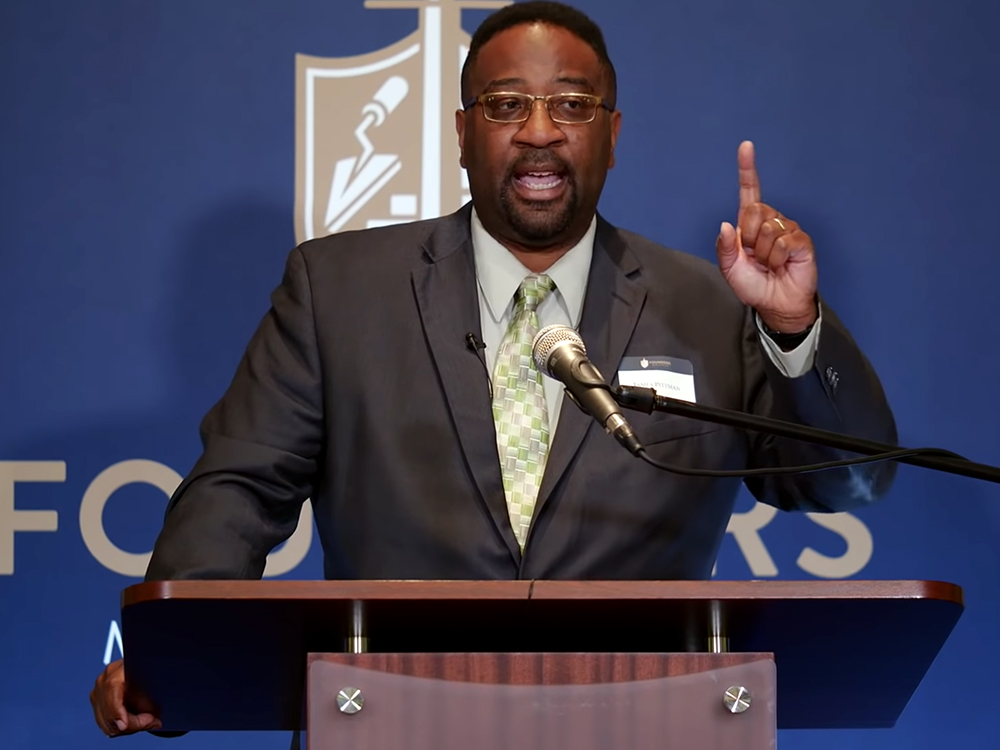

James Pittman speaks during a Founders Ministries event June 14, 2021, at the Founders’ “Be It Resolved” conference in Nashville, Tennessee. Video screen grab

There are some who see evangelicals’ pushback against racial and social justice as more political than theological, an effect of evangelicals’ adoption of the Republican Party to see their faith agenda reflected in U.S. law. The identities have merged, and as wokeness has become the calling card of the Democratic left, evangelicals oppose it as Republican loyalists.

Samuel L. Perry, associate professor of sociology at the University of Oklahoma, is one of those who say that the evangelical church’s war against wokeness shows that evangelicals are defined more by their politics than their faith. He pointed to data from Pew Research Center showing the growing number of people who identified as white evangelicals during the Trump era, including some who had been unaffiliated.

“I think the whole identity is being hollowed out by the culture war,” he said. “White evangelical is becoming this empty category that really just means friendly to religion and really conservative.”

In a 2020 speech to the Southern Baptist Convention’s Executive Committee, then-SBC President J.D. Greear, a North Carolina megachurch pastor, warned of the clash between the evangelical movement’s religious ideals and its quest for political influence.

“We are not, at our core, a political activism group,” he told fellow SBC leaders. “We love our country, but God has not called us to save America — he’s called us to build the church and spread the gospel and that is our primary mission.”

Greear was addressing division in the nation’s largest Protestant denomination over issues such as social justice and CRT, which have led critics to claim SBC leaders are woke and liberal. After the denomination’s seminaries declared that CRT was incompatible with the SBC statement of faith, several high-profile Black churches left in protest. Strachan, who once led the Council on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood, which is based at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, and taught at Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Kansas City, Missouri, left the denomination in part because he believes it has become too woke.

But the debates over “wokeness” and CRT aren’t really even about politics per se, Perry argues. Instead, they are debates over group identity and power. He pointed to the work of Lilliana Mason, a John Hopkins University political science professor, who writes about “affective polarization” — the idea that Americans are divided not by policy, but by how they feel about people who are different from them.

Americans are polarized around what Mason calls “mega-identities” — where their religious, political, social beliefs all merge. Those identities compete with each other, Mason argues, often driving people to political action out of dislike for those with other identities.

Labeling people as “woke” is not a statement about people’s ideas about police killings or race in general, Perry said. It is designed to trigger an emotional response, telling evangelicals and other conservatives that they are not to be trusted. “It’s ultimately a game of identifying boundaries,” said Perry.

But prying theology, politics and identity apart may be impossible. In his book, Strachan says that works on racism in the church, such as “The Color of Compromise” by Jemar Tisby, “Prophetic Lament” by Soong-Chan Rah or “Woke Church” by Eric Mason, are signs that wokeness has supplanted Christian theology. He is particularly critical of “Divided by Faith,” a 2000 book by researchers Michael Emerson and Christian Smith, which documented the racial divides among Christians who share similar beliefs.

Emerson, chair of the sociology department at the University of Illinois at Chicago, said he used to think white Christians and Christians of color were interpreting the same faith in different ways. Now he believes that the two groups are practicing different faiths with different beliefs, with white Christians holding to a version of the faith that supports their political and social power.