I live at latitude 44.9778° north, longitude 93.2650° west. If you’re not a geography or cartography geek (I’m not either), those are the coordinates for Minneapolis, Minnesota. Perhaps all “Minneapolis” means to you is cold. Some think Minneapolis is a suburb of the North Pole. Not quite true, but it feels like it sometimes.

With the return of December, winter is now bearing down on us. We Minnesotans will spend a considerable amount of the next four months managing snow, ice and frigid temperatures. Our furnaces have fired up and we’ve dug out our sweaters, coats, hats, gloves, scarves, boots, shovels and (for those fortunate ones) snow blowers. Once again we’re allowing extra time to brush snow and scrape ice off our cars before driving anywhere. We veterans of the tundra understand this very well: It takes a lot of work to stay warm.

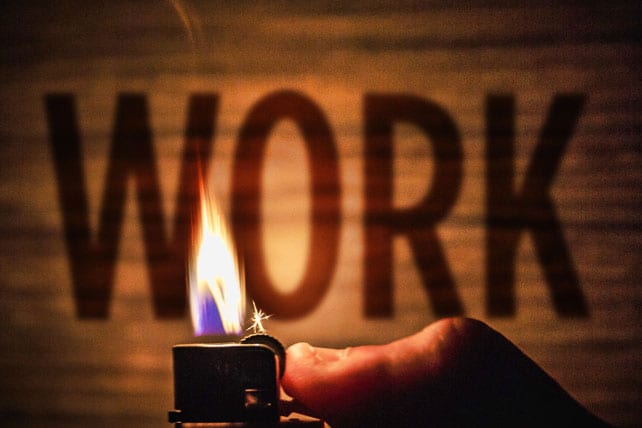

Fire: Key to Surviving the Cold

But 150 years ago it took a lot more work to stay warm during a Minnesota winter. I have great respect for the native peoples and settlers who endured the Lord’s cold (Psalm 147:17) before the days when natural gas was piped directly into homes equipped with automatic, thermostat-regulated heating systems. A sesquicentenary ago, most people had only one way to keep a house or teepee warm: Tend a fire.

Life during winter revolved around tending fire because fire was key to surviving the cold.

And tending a winter fire was a lot of work. It began during the warm seasons, because you had to think and plan ahead for the winter fire. You knew unpredictable snowstorms and severe cold were coming. You’d still have to do nearly everything you had to do in the summer, but everything would take longer in the winter, and you would have less daylight in which to do it. If you ran out of fire fuel in the bitter cold, you would be in trouble. So you were cutting down trees long before the first flurries, chopping them into logs, and figuring out ways to keep them secure and dry.

When winter hit, the fire was always on your mind, no matter what else you were doing. If you didn’t fuel the fire, it went out. If the fire went out, the temperature dropped quickly and it took a lot more—more wood, more work and more time—to reheat a cold room and cold furniture than to keep them warm in the first place. So every day, besides the rest of life’s demands, you split wood, restocked the fireside, kept the fire fed and cleaned out ashes. The fire was the first thing you tended in the morning and the last thing you tended at night.

Tending the fire was a lot of work, but it was necessary work because fire was key to survival.