4. Each believer must be fully convinced of their position in their own conscience (Rom. 14:5).

“One person esteems one day as better than another, while another esteems all days alike. Each one should be fully convinced in his own mind.”

The first great principle of conscience is that God is the only Lord of conscience. This point, however, brings us the second most important principle of conscience: obey it! God didn’t give you a conscience so that you would disobey it.

This doesn’t mean your conscience is always right. It’s wise to calibrate your conscience to better fit God’s will, which is why we have a whole chapter on conscience calibration in our book. But it does mean that you can’t keep sinning against your conscience and be a healthy Christian. You must be fully convinced of your present position on food or drink or special days—or whatever the issue—and then live consistently by that decision until God leads you by his Word and Spirit to adjust your conscience.

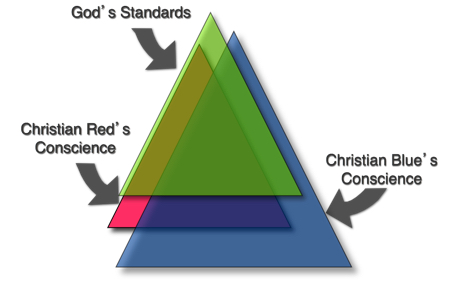

No two believers have exactly the same conscience. That’s why we need Romans 14! But the truth that needs to burn into all of our hearts is that no Christian has a conscience that matches God’s standards completely. No one.

5. Assume that others are partaking or refraining for the glory of God (Rom. 14:6–9).

“The one who observes the day, observes it in honor of the Lord. The one who eats, eats in honor of the Lord, since he gives thanks to God, while the one who abstains, abstains in honor of the Lord and gives thanks to God. For none of us lives to himself, and none of us dies to himself.”

Notice how generous Paul is to both sides. He assumes that both sides are exercising their freedoms or restrictions for the glory of God. Wouldn’t it be amazing to be in a church where everyone gave each other the benefit of the doubt on these differences, instead of putting the worst possible spin on everything?

6. Do not judge each other in these matters because we will all someday stand before the judgment seat of God (Rom. 14:10–12).

“Why do you pass judgment on your brother? Or you, why do you despise your brother? For we will all stand before the judgment seat of God; for it is written, ‘As I live, says the Lord, every knee shall bow to me, and every tongue shall confess to God.’ So then each of us will give an account of himself to God.”

If we thought more about our own situation before the judgment throne of God, we would be less likely to pass judgment on fellow Christians.

7. Your freedom to eat meat is correct, but don’t let your freedom destroy the faith of a weak brother or sister (Rom. 14:13–15).

“Therefore let us not pass judgment on one another any longer, but rather decide never to put a stumbling block or hindrance in the way of a brother. I know and am persuaded in the Lord Jesus that nothing is unclean in itself, but it is unclean for anyone who thinks it unclean. For if your brother is grieved by what you eat, you are no longer walking in love. By what you eat, do not destroy the one for whom Christ died.”

Free and strict Christians in a church both have responsibilities toward each other. But the second half of Romans 14 places the bulk of responsibility on Christians with a strong conscience. One obvious reason is that they claim to be strong, so God calls on them to “bear with the weaknesses of the weak” (Rom. 15:1). Not only that, of the two groups, only the strong have a choice in third-level matters like meat, holy days, wine, etc. They can either partake or abstain, whereas the conscience of the strict allows them only one choice. It is a great privilege for the strong to have double the choices of the weak. They must use this gift wisely by considering how their choices affect the sensitive consciences of their brothers and sisters.

In this principle, Paul shows an astute understanding of how conscience works. As we said, one of the two great principles of human conscience is “obey it.” To get into the habit of disobeying conscience can jeopardize one’s eternal destiny (1 Tim. 1:19). This truth leads Paul to spend half of Romans 14 and half of 1 Corinthians 8 on the stumbling-block principle: Christians with a strong conscience must not allow their freedom to embolden a weaker brother or sister to sin against their conscience.

The concern here is not merely that your freedom may irritate, annoy, or offend your weaker brother or sister. If a brother or sister simply doesn’t like your freedoms, that’s their problem. But if your practice of freedom leads your brother or sister to sin against their conscience, then it becomes your problem. We should never bring spiritual harm to others (see also vv. 20–21).

So, how might your use of freedom bring spiritual harm to other professing believers? Paul isn’t clear here, but Doug Moo in his commentary on Romans suggests “two main possibilities”:

[1] Our engaging in an activity that another believer thinks to be wrong may encourage that other believer to do it as well. They would then be sinning because they’re not acting “from faith” (v. 23). . . .

[2] An ostentatious flaunting of liberty on a particular matter may so deeply offend someone that he or she may turn from the faith altogether. (468)

True, we must never allow the conscience of others to determine our own conscience, since the most important principle of conscience is that God is the Lord of conscience. But we must always consider the conscience of others when we determine our own actions.

8. Disagreements about eating and drinking are not important in the kingdom of God; building each other up in righteousness, peace, and joy is the important thing (Rom. 14:16–21).