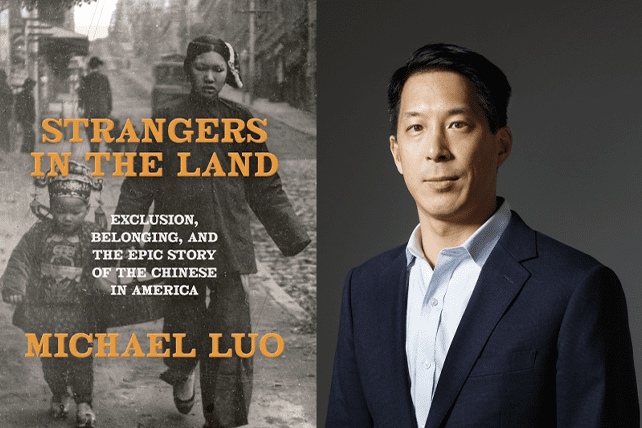

(RNS) — “Strangers in the Land,” the recently published book by New Yorker Editor Michael Luo, chronicles the journey of Chinese immigrants to the American West, and then eastward across the country. Perhaps inevitably, it is also an account of the violence and bigotry directed against them, which only became more intense as the boom years of the Western Gold Rush gave way to the economic downturn that followed the Civil War.

Christian clergy cast their own shadow over Luo’s narrative. Faith leaders — almost all of them white Protestants — were instrumental in shaping, not only the experience of the immigrant, but also the communities that sometimes welcomed, sometimes attacked them.

Asian American history is not, in general, part of the standard public school curriculum, nor have American historians paid much attention. “Until recently, U.S. historians largely ignored Asian immigrants and their U.S.-born descendants,” said Harvard University historian Erika Lee in her essay, “The Necessity of Teaching Asian American History.” “When they did appear in scholarly monographs or textbooks, they were little more than footnotes and dismissed as tangential to the making of the United States.”

Luo’s book, with its meticulously detailed cast of characters, makes a spirited argument that it is time to redress that imbalance, not only out of fairness to a minority group, but in order to reveal the central role Chinese immigrants played in the life of the nation. “The Chinese in America were not simply the victims of barbarous violence and repression; they were protagonists in the story of America,” Luo writes in the book’s introduction.

Passed in 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act, the first U.S. law approved on the basis of race, was not fully repealed until 1965, when a new immigration regime set aside quotas based on national origins, allowing large numbers of Chinese immigrants to settle in the United States. The earlier, mostly male pioneers who braved the unsanitary and often dangerous journey across the Pacific to find work were both defended and demeaned by Christian leaders, according to Luo.

Christian clergy and missionaries of the time “really modeled how to support and defend the most unlikable people,” said Tim Tseng, director of the Asian American Christian History Institute at Fuller Theological Seminary. “The Chinese were classified as the least likable.”

But many white pastors who show up in Luo’s book “had ugly views of the Chinese because they were, as they put it, heathens,” he writes. “You see this duality again and again.”

Both types of clergy were driven by the sense that the immigrants were not equal to the white population, suggested Cornell University historian Derek Chang, who directs the university’s Asian Studies program. “You don’t need to uplift or convert or transform a population, unless you think that somehow they are lacking something,” said Chang, author of “Citizens of a Christian Nation: Evangelical Missions and the Problem of Race in the Nineteenth Century.”

“This is very much a civilizing mission,” said Jennifer Taylor, a professor of public history at Duquesne University. Besides conversion to the faith, those who ministered to the Chinese community provided food and English lessons. Catechism was a facet of this larger assimilation.

The Rev. William Speer, who had spent four years in Guangzhou as a missionary, was recruited by Chinese residents of San Francisco in 1853 to advocate for them in the face of frequent violent attacks. While Speer praised Chinese civilization and history, Luo says, he believed it was America’s divine privilege to educate these “heathens,” as they had done with Africans before them.

In 1870, the Rev. Otis Gibson, another former missionary in China, founded the Women’s Missionary Society of the Pacific Coast with his wife. According to its constitution, its mission was “to elevate and save heathen women on these shores.” The mission’s third floor was set aside for Chinese women who had escaped prostitution or abusive situations as servants in the home, or who were prospective brides for the Chinese men who lodged them there, according to Luo.