“It’s not a tragedy that’s left in 1921. It’s a tragedy that continues to live each day that lacks justice,” said Turner, who protests weekly outside Tulsa City Hall, calling both for reparations and for a posthumous criminal investigation of the massacre’s perpetrators.

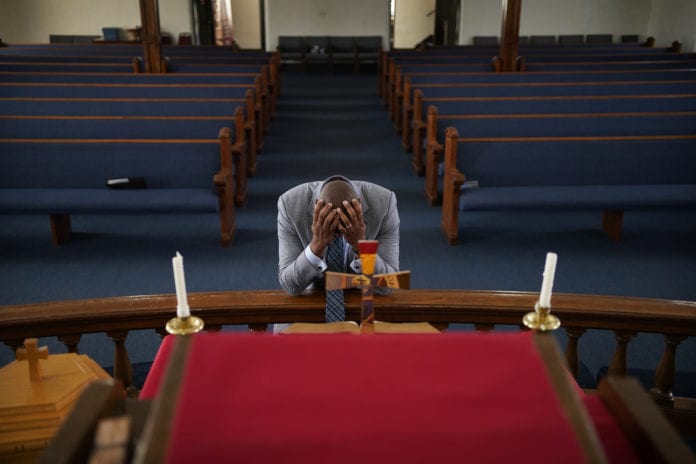

Some churches on Sunday recognized 13 still-active congregations that operated in Greenwood in 1921, including many that had to rebuild their destroyed sanctuaries. Lists of the 13, under the heading “Faith Still Standing,” are being distributed on posters and other merchandise.

“We don’t want it ever to happen again anywhere,” said the Rev. Donna Jackson, an organizer of the recognition.

Some historically white churches also observed the centennial.

Pastor Deron Spoo of First Baptist Church of Tulsa, a Southern Baptist church less than two miles from the similarly named North Tulsa church, told his congregation that the massacre has been “a scar” on the city.

The church has a prayer room with an exhibit on the massacre, accompanied by prayers against racism. It includes quotations from white pastors in 1921 who faulted the Black community rather than the white attackers for the devastation and declared racial inequality to be “divinely ordained.”

Spoo told congregants on Sunday: “While we don’t know what the pastor 100 years ago at First Baptist Tulsa said, I want to be very clear: Racism has no place in the life of a Jesus follower.”

Also recognizing the massacre was South Tulsa Baptist Church, a Southern Baptist congregation in a predominately white suburban part of Tulsa.

Pastor Eric Costanzo grew up in Tulsa but didn’t learn of the massacre until attending seminary out of state. When he later saw an exhibit on the massacre at the Greenwood Cultural Center, he recognized its enormity. He later got involved with centennial planning, arranging for presentations at the church about the massacre and visits by church members to Greenwood.

In an interview, he said he hoped that the “bridge we created between our communities” remains active after the centennial to confront “a lot of the hard topics our city and culture faces.”

The Rev. Zenobia Mayo, a retired educator and an ordained minister in the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), is also working to continue those conversations after the centennial. She said her family never used to talk about the massacre, even though her great-great-uncle, renowned surgeon A.C. Jackson, was among its most prominent victims.

Elders in the family sought to protect their children from the trauma of racist violence, she said. “They felt not talking about it was the way to deal with it.”

But now Mayo hopes to host discussions on racism at her home with mixed groups of white and Black guests.

“If it’s going to be, let it begin with me,” she said.

___

Associated Press religion coverage receives support from the Lilly Endowment through The Conversation U.S. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

This article originally appeared here.