Most people know C.S. Lewis through his books—perhaps “The Chronicles of Narnia,” or more explicitly theological works like “Mere Christianity“ and “The Screwtape Letters.” Through these and more than thirty other books, along with essays, radio talks, films, and theatrical adaptations, Lewis has shaped the faith of millions.

Far fewer people know the man behind the books.

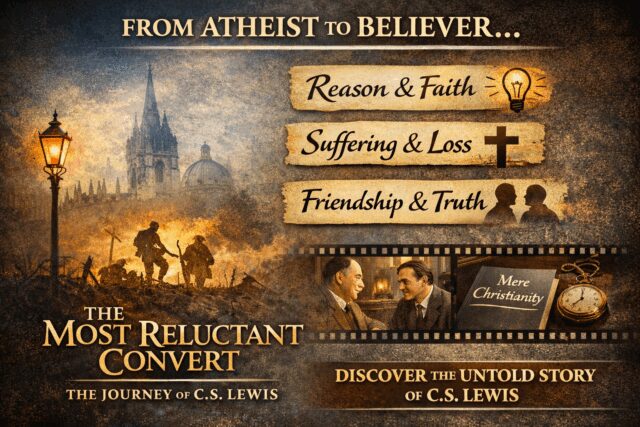

That absence is what first compelled me to step inside Lewis’s life—not as a scholar, but as a storyteller. I wanted to understand how a man who so fiercely resisted Christianity came, against his will, to become one of the most influential Christian writers of the twentieth century. That exploration eventually became “The Most Reluctant Convert,” first as a stage production and later as a feature film.

Lewis was not looking for God. By his own admission, he was doing everything he could to avoid him. And yet, at the age of 31, Lewis came to believe—not through spectacle or sentiment, but through friendship, suffering, reason, and time. His story reminds us that conversion is rarely tidy, rarely quick, and almost never proceeds along the lines we would choose.

From Lewis’s life, three truths stand out—truths that remain deeply relevant for anyone who loves a “reluctant convert.”

1. Reason and Intellect Are Not Enemies of Faith.

C.S. Lewis spent the first three decades of his life convinced that Christianity could not survive serious scrutiny. Reason itself, he believed, had rendered God unnecessary. But Lewis eventually discovered that reason requires a foundation reason alone cannot supply. If our thoughts are nothing more than the accidental result of atoms colliding in the brain—unconnected to any “fuller, more perfect life”—then reason is merely a predetermined byproduct of physics and biochemistry. In that case, we never think a thought because it is true, but only because blind forces compel us to think it.

Lewis concluded this was absurd. Far from abandoning his intellect, he came to see that belief in something “further up and further in” was the only thing that made rational thought intelligible.

2. God Is Sovereign Even in Painful Circumstances.

Lewis lost his mother at a young age, a loss that shattered his early faith and hardened his resistance to God. He later endured the brutality of the First World War—“the hell where youth and laughter go”—and carried physical and emotional wounds long afterward. For years, these experiences seemed only to confirm his belief that the universe was indifferent, if not cruel.

Yet Lewis eventually realized that the very experiences he used as arguments against God were also the means by which God was drawing him closer. “My argument against God,” he wrote, “was that the universe was cruel and unjust. But how had I got this idea of just and unjust? I call a line crooked because I know what a straight line is.” If the universe has no meaning, Lewis asked, how would we even know it was meaningless?