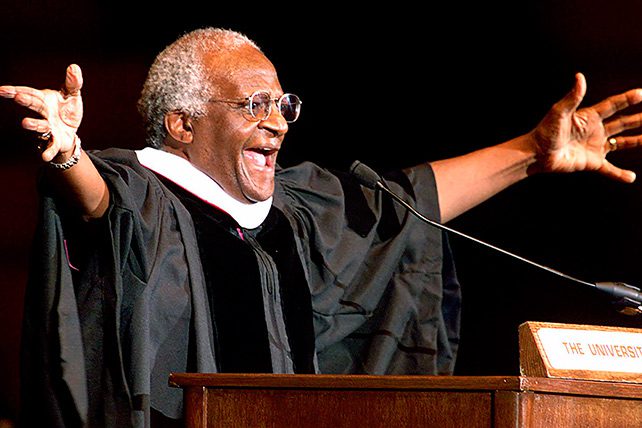

(RNS) — Retired Anglican Archbishop Desmond Mpilo Tutu, the man who became synonymous with South Africa’s nonviolent struggle against apartheid, died Sunday (Dec. 26) at the age of 90.

Tutu was diagnosed with prostate cancer almost two decades ago.

The feisty spiritual leader of millions of Black and white South Africans seized every opportunity at home and abroad to rail against the racially oppressive regime that stifled his country for decades. His struggles earned him the Nobel Peace Prize and appointment to the leadership of a commission that sought to reveal the truth of apartheid’s atrocities.

“There’s no person on the face of the earth — Nelson Mandela would have been the other — that has had the kind of moral compass and exemplary mandate I think that the archbishop has,” said Alton B. Pollard III, former dean of Howard University’s School of Divinity.

In later years, Tutu carried his work for justice into other areas beyond racial reconciliation — from AIDS to poverty to gay rights.

“All, all are God’s children and none, none is ever to be dismissed as rubbish,” he said in 1999 to the “God and Us” class he taught as a visiting professor at Emory University’s Candler School of Theology. “And that’s why you have to be so passionate in your opposition to injustice of any kind.”

RELATED: Beth Moore Serving Eucharist at Her New Anglican Church Causes Twitter Meltdown

Long before South Africa elected its first democratic government in 1994, Tutu dreamed of and spoke fervently about “what it will be like when apartheid goes.”

But there were times in public speeches and in interviews when the cleric doubted whether, after decades of agitating for social justice, he would live to witness the decay of apartheid.

During the 1970s and ’80s, when other Black leaders critical of white majority rule were being violently snuffed out or silenced, Tutu’s prominence in the church made his one of the few Black voices strong enough to resonate around the world.

But at times, not even his stature in the church or powerful international religious connections were enough to keep the government at bay or from confiscating his passport. Protests by the world’s leading clerics, including the Archbishop of Canterbury, came but failed to buffer Tutu from the brutal regime.

Tutu said a disciplined prayer life helped him through apartheid and continued to sustain him decades later.

“I could myself not have survived had I not been buttressed by my spiritual disciplines of prayer, quiet and regular attendance at the Eucharist,” he told Religion News Service in 2011.

His bold protests against racial segregation and public campaigns for international economic sanctions made Tutu a thorn in the side of the South African government. But to many Blacks in the country, Tutu wasn’t radical enough. Some even chided him for being dedicated to crafting a nonviolent resolution with whites for racial reconciliation in South Africa.

Tutu never set out to be a controversial figure or even a priest.