(RNS) — Many Asian Americans are tired of being told who they are. Nerdy overachievers. Perpetual foreigners. Quiet and submissive. Interchangeable. Too proximate to whiteness to experience oppression, but too nonwhite to be included.

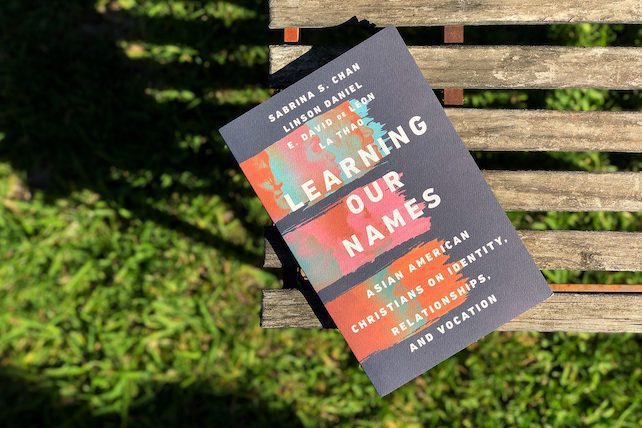

For decades, members of Asian American communities have been reckoning with labels they didn’t choose for themselves while having their names mispronounced or changed altogether by those who didn’t care enough to get them right. For the authors of “Learning Our Names,” a new book from InterVarsity Press published Aug. 30, recovering their names has been a way to both embrace their Asian American stories and their identities as children of God.

“Our names, whether their origins are clear or obscure, provide an opportunity for us to look back and make meaning,” the authors write in the first chapter. “Looking back helps us locate ourselves in our family’s story and in God’s story.”

Amid an unprecedented escalation of anti-Asian hate crimes — which increased 339% in 2021, according to the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism — authors Sabrina S. Chan, Linson Daniel, E. David de Leon and La Thao invite readers into the richness and complexity of Asian American experiences, all from a Christian lens. Integrating unique elements from their East Asian, Southeast Asian and South Asian backgrounds, the authors combine personal stories with research and biblical texts to provide a powerful tool for discernment.

Religion News Service spoke with three of the authors about the book and their experiences as Asian American Christians. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why call your book “Learning Our Names”?

Chan: Many Asian Americans have experiences of their names being mispronounced or people not even trying to learn their names, because a lot of our names are seen as foreign or too complicated. It’s an invitation both to Asian Americans to continue to learn our names together and to non-Asians to say, what does it look like for you to learn our names and learn something about us?

Can you talk about the biblical story of Hagar and how it relates to this idea of names?

De Leon: Womanist interpretations of Hagar drew me to think about the parallels between Hagar and various levels of marginalization Asian Americans experience. There is agency Hagar expresses when she names God as the God who sees. Hagar is naming God in light of her needs and in light of her story. And I think that image is one that is important for Asian Americans as we assert our identities and name God as the God that we need in light of the hostile world that America is.

Chan: I’m drawn to the part where Hagar is seen by God because Asian Americans have a kind of strange relationship with being seen. There’s a hyper visibility at times when you’re seen as a foreigner, and then there’s an invisibility when our stories aren’t acknowledged. The author of Genesis outlines Hagar as a foreigner and mentions multiple times that she’s an Egyptian. But then there’s also invisibility because Abram and Sarah never call her by her name. She’s just the slave girl. So there’s this real connection with God knowing our names, even if other people don’t or don’t care to try and learn.

Why did you ultimately land on using the term “Asian American” for your book?

De Leon: Asian American encapsulates diasporic peoples from South Asia, Southeast Asia and East Asia. There’s obviously some strands of shared story and history, but not everyone’s story is the same. And even modern nation states fail to capture the diversity of cultures, tribes and ethnic communities within their own borders. For that term to do that work in the context of the U.S., where Asian Americans as a sociopolitical term can be conflated with race, is a challenging thing. But the legacy of the label itself is one of solidarity that came out of the 1960s and ’70s, where rather than accepting the perpetual foreigner model, Asian Americans began to assert their political identity.

Our book tries to both problematize Asian American identity for the ways it’s been exclusive, flattening or essentializing, and make it more breathable for people who might not fit into the American imagination of what an Asian American is.

How have the model minority and perpetual foreigner stereotypes shaped your experience with spirituality?

Thao: In some Asian American communities, at least mine in the Hmong American community, it feels like being a Christian contributes to this sense of being a model minority. It can make you feel more American, and you can feel a sense of superiority as a Christian. Because of this model minority mentality within the church, I think that’s why I didn’t know a lot about my own culture, which was harmful for me as I was developing my own identity.