CHAPEL HILL, N.C. (RNS) — Sandy Wong still cries when she tells the story.

A few years ago, she registered to attend a women’s retreat at her church, Chapel Hill Bible Church, where she had worshipped for close to 20 years. A Taiwanese immigrant and a mother of three adult children, she often volunteered to help care for children during services and other events. “I love kids,” she said. “They make me happy.”

But on the day of the retreat, the mostly white attendees asked if she would look after their children instead of participating in the gathering.

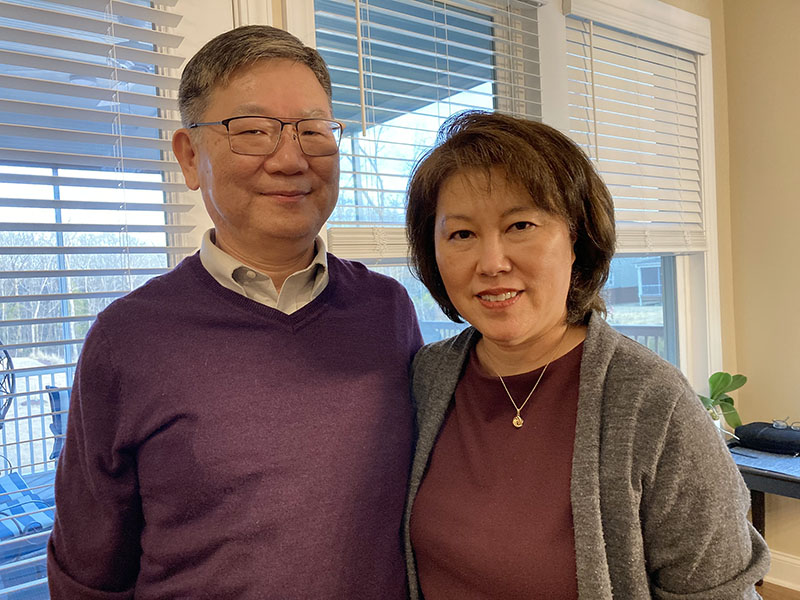

It wasn’t the first such humiliation for Wong, who often felt as if her race prompted fellow church members to think of her as the “help.” She was so distressed, she moved temporarily to Rockville, Maryland, where she and her husband, Tin-Lup Wong, own a townhouse. In December she moved back, and in early March the couple penned a letter of resignation to the congregation.

RELATED: Missional and Multiethnic: Are You Ready for the Future of the Church?

”Now we realize what we experienced was racial discrimination,” the Wongs wrote.

The Wongs are among as many as 200 people who have left Chapel Hill Bible Church in recent months — more than 20% of this once flourishing nondenominational congregation in the university town. Several have shared stories similar to the Wongs’.

Sandy and Tin-Lup Wong resigned from Chapel Hill Bible Church in March, saying the church racially discriminated against them. They are pictured in their Chapel Hill home on March 14, 2023. RNS photo by Yonat Shimron.

They say church leadership over the past several years has turned inward, drawing boundaries around orthodox beliefs and dismissing or demeaning members’ concerns. That has led to the departures of many families of all races who complained of the church leadership’s lack of transparency and care.

But the loss of nonwhite members has been especially pronounced, especially since white evangelical Christian congregations have made efforts in recent years to repent of the sin of racism and court a younger, more multiracial generation. A 2020 study found that the proportion of evangelical congregations that were multiracial nearly tripled, to 22%, in 2018-19, up from 7% in 1998.

“There’s an absolutely sincere desire to get this right,” said Molly Worthen, a professor of history at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill who writes frequently about evangelicals. “A large swath of conservative evangelicals are engaged in this conversation. My sense was that Chapel Hill Bible Church was in that mix.”

RELATED: Faith Groups Focus Midterms Mobilization on Multiracial, Multifaith Voter Protection

The Bible church seemed perfectly positioned to attract a diverse membership, and for many years it did, boasting that 20% of people attending were nonwhite. Jay Thomas, hired as pastor in 2011, is himself biracial; he was born in India and came to the U.S. as a boy.

Many of those nonwhite members were Asian, reflecting Chapel Hill’s demographics: 13% of the town’s residents are of Asian origin, according to the U.S. Census, making them the town’s largest minority group. (Blacks constitute 10% of the population).

But during Thomas’ time as pastor, Chapel Hill Bible has reversed years of interracial progress.

Young and Sarah Whang were members at Chapel Hill Bible Church for more than 20 years. RNS photo by Yonat Shimron

“Sadly, we came to the realization that our church gives lip service to diversity but fails to engage and empathize in a real way with people of color,” Young and Sarah Whang, a Korean American couple, wrote in their resignation letter last year.

The church declined to respond to a reporter’s inquiries.