(RNS) — The surviving relatives of the late Pope Benedict XVI stand to inherit money from his legacy, according to the executor of his last will and testament. None of these relatives seem willing to touch it.

One cousin has already refused to accept the inheritance; four others have not yet responded. If they are smart, they will turn it down as well.

The problem is that, by accepting the money, an heir also takes over any legal claims against the deceased, according to estate laws in Germany, where the cousins all live. Joseph Ratzinger, as he was known before adopting his papal name, is a defendant in one of the most-watched cases of clerical sexual abuse in the country.

“We didn’t expect this inheritance, and our lives are just fine without it,” said Martina Holzinger, the daughter and legal guardian of a now 88-year-old Ratzinger cousin who has refused the unexpected gift.

RELATED: What To Expect at the Funeral Mass for Emeritus Pope Benedict XVI

When the retired pope died at age 95 on December 31, 2022, his longtime assistant, Archbishop Georg Gänswein, got to work as executor of the will. “Gorgeous George,” as the Clooney-double was known among Vatican journalists, duly went about contacting the few first cousins still alive.

Without even knowing how much the inheritance would be, the prospect of taking on the scandal that darkened Ratzinger’s legacy was too much. “I could get the shakes just thinking about how much I would have to pay out,” she told Bavarian Radio.

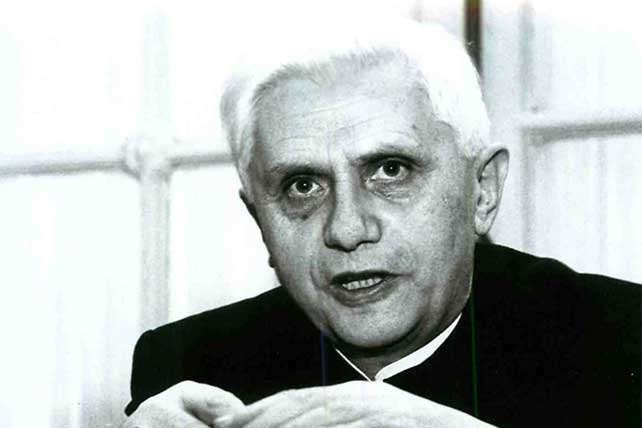

With the towers of the cathedral in the background, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, later Pope Benedict XVI, bids farewell to the Bavarian believers in downtown Munich, Germany, Feb. 28, 1982. The Vatican on Jan. 26, 2022, strongly defended Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI’s record in fighting clergy sexual abuse and cautioned against looking for “easy scapegoats and summary judgments,” after an independent report faulted his handling of four cases of abuse when he was archbishop of Munich. (AP Photo/Dieter Endlicher, File)

The former pope’s problems began in 1980, when he was archbishop of Munich, and the Rev. Peter Hullermann was transferred to the Bavarian state capital from Essen. Hullermann had been accused of eight cases of abusing children in Essen, but while Munich was informed of his record, the public was not.

After some therapy — the church’s accepted response at the time — Hullermann was sent back into normal ministry near Munich, with no mention of his past problems. That gave him access to minors once again, and by 1986 he received an 18-month suspended sentence from a local court for sexually abusing 11 boys.

Then the priest was sent to Garching an der Alz, near the Austrian border, and the abuse continued. In 2008, he was transferred again, to Bad Tölz, a spa town south of Munich. There, in 2010, he was suspended as a priest and finally defrocked in 2022.

The former pope denied knowing about Hullermann until January 2022, when a report on sexual abuse in the Munich archdiocese showed he had attended a 1980 meeting about Hullermann’s transfer and approved it.

The report, ordered by the archdiocese itself, accused him of probably lying to the investigators. They concluded Ratzinger had failed to act in four separate abuse cases.

Days later, his personal secretary, Gänswein, said Ratzinger now remembered attending the Hullermann meeting and blamed the omission on “an oversight in the editing of the statement.”