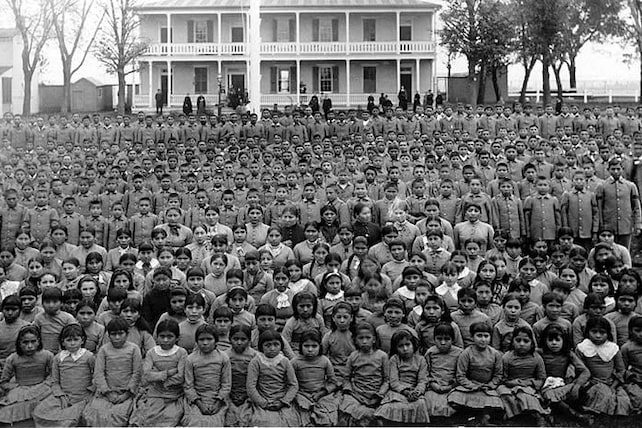

Chanar attended a government-run boarding school in the 1960s, taking four flights on small aircrafts from her Athabaskan village of Minto, Alaska, to reach the island town of Sitka. With no phone available, the teenage Chanar wouldn’t speak to her parents again for nine months.

At Mount Edgecumbe High School, she made lifelong friends from all over Alaska and received an education that would have been impossible back home, where there was no electricity and no high school, though each summer Chanar went back for a season of “hunting, fishing and living off the land.”

Despite the benefits, boarding school could be “really lonely,” she recalled. Her Athabaskan language skills deteriorated and she missed taking part in traditional events such as a memorial potlatch with singing and dancing to honor deceased loved ones.

“Those things that we did in the village—we couldn’t do that anymore,” Chenar said.

Now, she wants everyone with a story to be heard. She wants land returned, especially if it came from Indians and is no longer used as a church school. And because boarding schools often buried children lost to tuberculosis outbreaks and other causes, she wants all their remains located, exhumed and returned to families.

“If we don’t do this work, then what will happen?” Chenar said. “Will they just remain out there and a shopping mall will be built over them? Somebody’s got to be their voice. And if nobody’s going to step up, then yeah. I’m here. I have a voice. I’ll speak for them.”

COMMENTARY: The urgent need for a truth and healing commission on Indian boarding schools

The quest is rife with challenges. Locating records in obscure archives will require tenacity. Layers of church bureaucracy could cause delays, Chenar said, if approvals take a long time to get. In most regions where records were sought in the past, access was denied, according to Tadgerson. Advocacy for the work and why it matters will be an ongoing priority.

But commission chairs say they’re encouraged by the bishops’ initial responses. Many have offered to help in whatever way is needed, Chenar said. Meanwhile, community talking circles and panels are cropping up to help get testimonies on record, according to Tadgerson.

“Now that so many individual churches and religious leadership stakeholders are choosing to listen and support survivors and their loved ones,” Tadgerson said in an email, “restorative justice research can begin.”

This article originally appeared on ReligionNews.com.