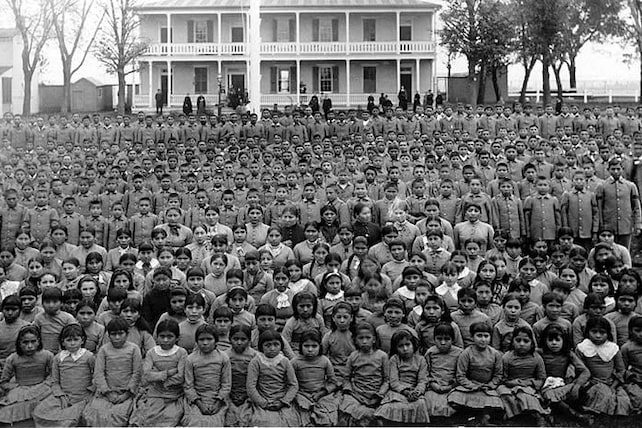

Beyond the number of its schools, Episcopalians and their church “played a uniquely transformative role” in creating the federal government’s Carlisle Indian Industrial School, according to Veronica Pasfield, a Native American researcher and archival consultant. Carlisle became the prototype for U.S. residential schools under Richard Henry Pratt, an Army officer who’d fought Indians on the Great Plains. Episcopalians in the Dakotas reportedly helped recruit students for the school.

“Federal and Church power worked collaboratively to operationalize Indian policy via schools that removed children from home for indoctrination and extraction,” writes Pasfield in a May consulting proposal. She’s now helping guide the church’s boarding school research.

“Indigenous Episcopalians are leading the process to uncover and tell the story of Episcopal Church involvement in Indigenous boarding schools, and that work, as they note, is just beginning,” said Episcopal Church spokesperson Amanda Skofstad in an email. “An apology before thorough research and understanding would fall short of the truth-telling, reckoning, and healing we committed to as a church.”

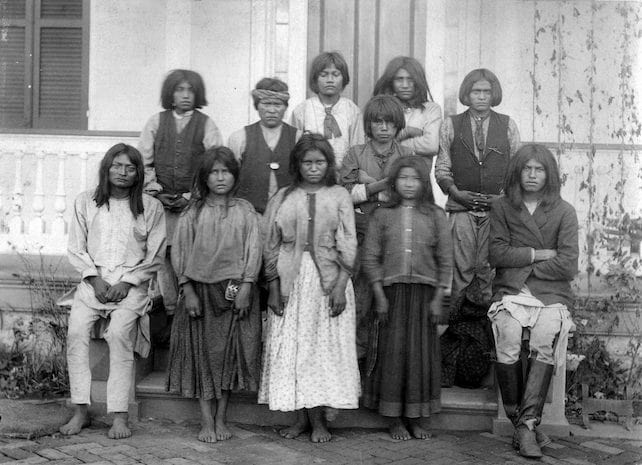

What emerges, scholars say, could reframe the church’s self-understanding. A traditional view holds that missionary educators had good intentions: to help Native Americans survive and flourish among white settlers by embracing Christianity, learning to own property individually and developing marketable skills. But such assumed benevolence needs to be questioned, according to Farina King, associate professor of Native American studies at the University of Oklahoma.

“It’s pulling down the narrative that was pushed for so long that these schools were all for the benefit of the people and the children,” said King, a citizen of Navajo Nation and author of “The Earth Memory Compass: Diné Landscapes and Education in the Twentieth Century.” “They were not what they pretended to be: for the good of Native peoples. They were really for the good of the dominating white American officials and Christian leaders.”

To grow enrollment at Carlisle, which garnered funding on a per-pupil basis, Pratt recruited Sioux students in South Dakota with high-pressure tactics and help from church leadership, according to historian David Wallace Adams in “Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience, 1875–1928.”

Episcopalian titans of industry, including the Vanderbilts, Jay Gould and J.P. Morgan, also benefited from the policy that included schools, building “opulent mansions from the profits of their railroads and extractive businesses on lands recently cleared of Indian people,” writes Pasfield, whose great-grandmother attended Mount Pleasant Indian Industrial School in Michigan.

“Indian boarding schools were tools for U.S. nation-building,” Pasfield writes. “They funded the reach and enhanced the wealth of Christian missions. As the archives show, boarding schools were a tool for dispossessing Indian families and impoverishing the future of Indian children and communities.”

Some regard what happened through the schools as attempted genocide that merely traded the costly warfare of an earlier time for cultural erasure in schools. Leora Tadgerson, an Indigenous Episcopalian who chairs one of the commissions, refers to the boarding school period as “the genocidal era.”

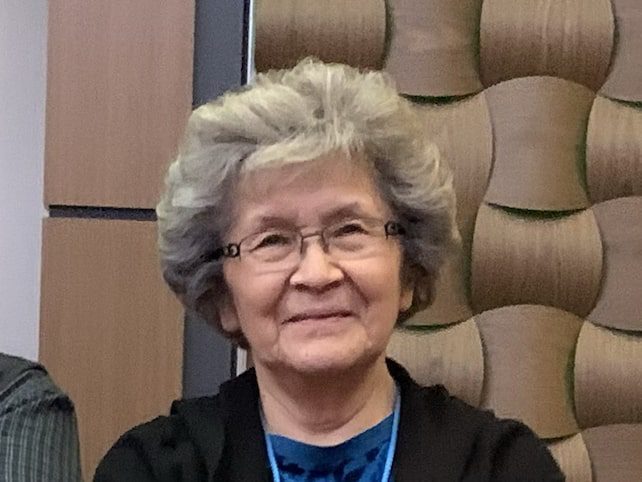

Pearl Chanar, an Athabaskan tribal member and co-chair of one of the two commissions, believes it all needs to come out, no matter how complicated, shameful or mixed the history might be.

“In order for everyone to heal, number one: The church has to acknowledge and apologize for what happened,” said Chanar, who lives in Anchorage, Alaska. “And number two: They have to do something about it. They can’t just receive the report, look at it and do nothing.”