3. Conversion Is Rarely a Solitary Event.

Lewis did not come to faith because of a single argument or a single person. He came because of many people, many conversations, many books, and many years.

As Lewis later put it, all his books were beginning to turn against him. The stories that had once fortified his unbelief now betrayed it. The pattern of dying and rising gods—familiar from pagan myth across cultures and centuries—kept resurfacing. Instead of explaining Christianity away, these myths began to suggest that the Gospel was not an isolated invention, but the fulfillment of something humanity had been telling itself all along.

At the same time, Lewis found himself increasingly surrounded. Among the Oxford faculty, Tolkien, Dyson, and Coghill were all Christians. “These queer people,” Lewis remarked, “were popping up on every side.” Even more unsettling was the fact that some of the most compelling appreciations of the Gospel came from unbelievers. One atheist colleague admitted that the story of Christ was profoundly moving—even if he could not bring himself to believe it.

That admission lodged itself in Lewis’s mind. Why should a story invented to deceive have such power to illuminate? Why should it resonate so deeply, even when people insist on running from its claims? Lewis began to see that the impulse was not to dismiss the Gospel as trivial, but to flee from it because it demanded too much. The story did not merely ask to be admired. It asked to be obeyed.

What Lewis was discovering, reluctantly, was that the problem was no longer whether Christianity was compelling. It was whether he was willing to surrender to it.

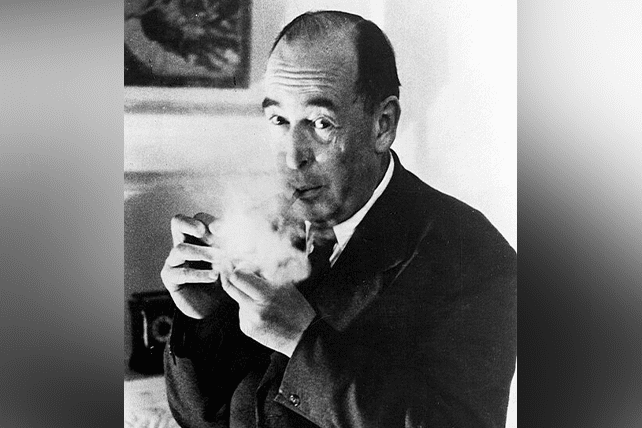

Ultimately, he did. Walter Hooper later described Lewis as “the most thoroughly converted man” he had ever known. We are the beneficiaries of that conversion.