Expository Faithfulness and Racism

Attention prominent White pastor: If you want to avoid controversy, do not preach sermons on race at large evangelical conferences. In 2018, that will not go well for you. This week, David Platt discovered this at Together for the Gospel (T4G) in Louisville, Kentucky.

Tasked with the responsibility of preaching on race and the church in America, Platt walked attendees through Amos 5:18-27, which includes the oft-cited King speech mantra to “…let justice roll down like waters, and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream.”

Platt told attendees that God used Amos to indict his people on three primary offenses: (1) eagerly anticipating future salvation, while conveniently denying present sin; (2) indulging in worship while ignoring injustice; and (3) carrying on their religion while refusing to repent.

Platt went on to apply the text to attendees, specifically mentioning racism as sin. He noted the complicity of the church in America in widening the racial gap in the United States. How? Being slow to speak about the various forms of racial injustice happening in America. He closed his message with a Christ-exalting call for repentance and an exhortation that one day Amos 5:24 will be fully realized in God’s coming kingdom.

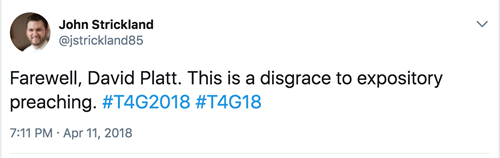

Platt began his talk asking for grace while handling a tough topic. Instead, some responses to his message were anything but gracious.

What did Platt say that led to this pushback? Why was his faithfulness to expository preaching questioned? Unfortunately, this is the moment we live in. For some, faithful exposition of a text means never preaching about racism from the pulpit. For some, preaching the whole counsel of God excludes sermons on racism in the church in America.

The writings of the prophets—both major or minor—are filled with calls for justice. This is especially true of the text in Amos 5. To question Platt’s faithfulness to the text ignores the broader issue at play here: a perceived attack on White identity.

In the message, Platt asks three very pointed questions: Why are so many of our churches so white? Why are many of our institutions, seminaries, and missions organizations so white? Why is (the T4G Conference) so white? All three questions are necessary for any Christian thinking through the impact of race on the church in America.

However, those questions were likely deemed offensive to those who had a problem with the talk. Rather than eliciting the desired introspection, the message caused some to decry what they felt were Platt’s proof-texted, subjective thoughts on racism in America. Some articulated a need to place racism in a clear, objective category like other sins. Otherwise, racism becomes much more difficult to identify and remedy. Because racism, at least for some, lacks a clear definition, it leads to frustration in pursuing justice. But do we need a clear definition of racism?

Pornography and Racism

In Jacobellis vs. Ohio (1964), the Supreme Court ruled on whether the state of Illinois could ban speech in a film it had deemed obscene without violating the First Amendment rights of a citizen. A deeply divided Court ruled that the speech in question was not obscene.

Justice Porter Stewart’s concurring opinion delivered probably the most famous Supreme Court quote to date. He wrote, “I shall not today attempt to further define the kind of material I understand to be embraced within (obscene speech in film)…But I know it when I see it…”

When asked to place racism in a clear, objective category, some African Americans want to throw up their hands and join Justice Stewart in saying, “We know it when we see it.” And others should know it when they see it too. Racism is not a moving target. It has plot points found in our prisons, housing, and workplaces. Those plot points are clear, but still find themselves mired in language of “individual accountability” as opposed to seeing much of it for what it is—systemic injustice.