(RNS) — Kevin Sack had spent decades covering Black churches for The New York Times, so when he heard about a shooting at Mother Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, he knew this was no random act of violence. “As soon as it was broadcast that this was an African Methodist Episcopal church, my heart just sort of sank.”

After the murderer of the nine Black churchgoers was revealed to be a white supremacist, Sack was determined to tell a much broader, book-length story of the church, its denomination and the racial tensions that shaped both. The result is “Mother Emanuel: Two Centuries of Race, Resistance, and Forgiveness in One Charleston Church,” released June 3, days before the 10th anniversary of the massacre.

“When I explained to people that one of my goals was to make sure that the church wasn’t forever known only for what happened on the night of June 17, 2015, I think that resonated with members of the congregation who had a real appreciation for everything that had come before,” he told Religion News Service in an interview, “and felt that the remarkable drama of that story should not be lost in the horror of one night.”

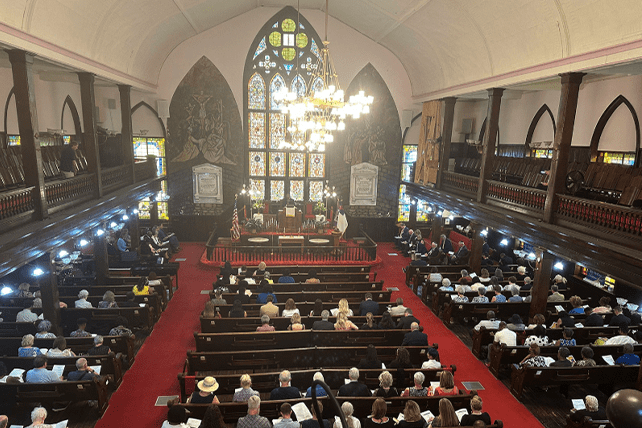

The author spent the last decade unpacking the evolution of the Charleston church that once dominated the city with thousands of members. Like many historic churches, it has faced declining membership while grappling with expensive repairs to its aging building.

Sack, 65, now a freelance journalist, talked with RNS about the complexity of forgiveness for Black Americans, the political use of Mother Emanuel’s pulpit and how the Charleston church overcame its initial wariness about a white outsider’s presence there Sunday after Sunday.

The interview was edited for length and clarity.

How’d you come to write this book about Mother Emanuel AME?

I went to Charleston for the Times to cover some of the aftermath. I wrote a long profile of (the Rev.) Clementa Pinckney and covered the eulogy (for him), in which President Obama sang “Amazing Grace.” I was starting to get familiar with the basic outlines of the church’s history and found that it had been the first AME church in the South and had this really interesting backstory almost at every point along, in the case of the church, the 200-year struggle for equal rights in this country.

Your book addresses the complicated topic of forgiveness, specifically related to Black Americans and Black churchgoers. How would you sum up what you concluded about that topic, specifically for Mother Emanuel and more generally?

I concluded that the forgiveness that was expressed by family members toward the killer wasn’t really for the killer; that it was more for themselves. After interviewing them extensively and speaking to theologians and folks on all sides of the forgiveness debate that emerged in Charleston, I decided that it really was more a form of release for those who forgave than a prayer for the soul of this unrepentant sinner. I started to understand that forgiveness in the context of the African American experience and in the context of Black Christianity really was more about a reclamation of agency. I assert that forgiveness in this context is really its own form of resistance, that it is a way to reassert power, when something of significance has been robbed from you.

“Mother Emanuel: Two Centuries of Race, Resistance, and Forgiveness in one Charleston Church” by author Kevin Sack. Image courtesy of Sack

You write that the Rev. Richard H. Cain, who helped build Emanuel AME in the 1860s, was a prominent preacher and a politician, including state senator, just like Rev. Clementa Pinckney. Do you see other parallels in the early leadership and the leadership at the time of the massacre at Mother Emanuel?

Cain was the pastor who revived the congregation in 1865 after the Civil War. He used Emanuel’s pulpit as a springboard into business, into publishing and into politics, running successfully for the state Legislature and ultimately for Congress. His career really sort of traces the arc of Reconstruction, both this incredible hope at the beginning, and the crushing of that hope at the end. And then there were very political speakers at the church over time. Booker T. Washington in 1909, W.E.B. DuBois in 1921, Dr. (Martin Luther) King in 1962. So when Pinckney becomes the pastor as a very highly regarded state senator, he’s following in the line of a long history of political activity from that pulpit.

You note the conservatism of the wider African Methodist Episcopal Church, even as some of its pastors have been progressive advocates for voting and other civil rights. How has Mother Emanuel reflected that dualism even to this day?

I found that all so curious and so interesting that these liberationist churches were also socially conservative, particularly on issues related to gay rights and same-sex marriage. And Emanuel reflects that in every way. I asked around pretty broadly and have yet to find anyone who would tell me of an openly gay member of the congregation, not just now, but ever. That doesn’t mean, obviously, that there aren’t LGBTQ members of the congregation, but nobody advertises it, and the denomination does not countenance same-sex marriage by its pastors, on threat of defrocking.