While religious liberals may have reduced as a share of the overall population, Braunstein points to a recent report examining data from the Cooperative Congressional Election Study that found liberal-leaning religious activists are “the most active group in American politics.” When combined with an uptick in media reports focused on the movement — ranging from The New York Times to Politico — Braunstein couched this phenomenon as yet another “narrow backlash” in response to the religious right.

“There is heightened positive attention to groups like the religious left,” she said. “We saw that during (former President Donald) Trump’s presidency and during campaign seasons — including a recent New York Times column where Nicholas Kristof … said how excited he is that the religious left is more visible and prominent, to provide a kind of religious counter ballast to the religious right. I think we’re seeing it in the form of Democratic presidential candidates, talking openly about their faith and about the important role their religion plays in shaping their commitments to things like justice and equality.”

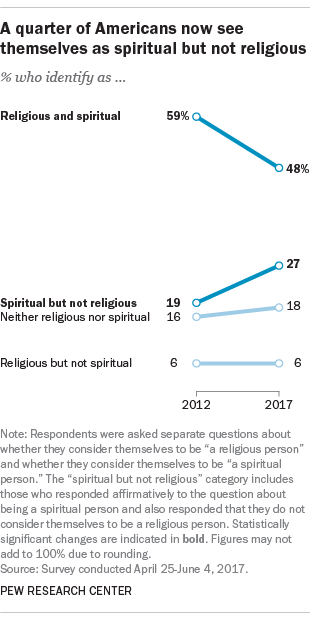

Graphic courtesy of Pew Research Center

Braunstein then pointed to a final narrow backlash: a tendency among some liberal mainline traditions to decouple political activism from religion. She explained it as a shift not so much in religious affiliation or ideals as an overall tweak to the words used to describe them.

“This scenario differs from a broad backlash in that people remain committed to the religion field, but nonetheless frame their depoliticized version of religious expression as a positive alternative to politicized conservative religion,” she writes. She added that while this approach shares the religious left’s desire to reject the association of religion with conservative politics, “it does not do so by publicly embracing the fusion of religion and liberal politics, but rather by delinking religion from all politics.”

But as liberals — and particularly religious liberals — responded to the religious right over the decades, Braunstein says, something else was happening to the religious right itself: It experienced the effects of a counter backlash, a “feedback effect” that leads to “doubling down” in the face of criticism.

The result was the development of what Braunstein called a “purification process” among politically active conservative Christians in general, and white evangelicals in particular. When more moderate voices in their fold challenged campaigns against abortion and same-sex marriage — or, more recently, support for Trump and his broader political movement — they were often excised. She pointed to Russell Moore and Beth Moore (no relation), both prominent Trump critics who received significant backlash from fellow evangelicals. They both left the Southern Baptist Convention last year: Beth Moore, an author and Bible teacher, publicly left the SBC altogether, whereas Russell Moore resigned from his lofty position as president of the denomination’s ethics commission and began quietly attending a church unaffiliated with the SBC.

“Because of the effort to purify their group and be less tolerant of political dissent within their communities, we’re seeing high profile and everyday examples … being pushed out of evangelical communities because they question the political kind of choices of that community,” she said.

What’s left is a religious right with “fewer checks on radical ideas,” she said. It can have dire results: She cited those who have embraced the Christian nationalism on display during the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021.

In this Jan. 6, 2021, file photo, a man holds a Bible as Trump supporters gather outside the Capitol in Washington. The Christian imagery and rhetoric on view during the Capitol insurrection are sparking renewed debate about the societal effects of melding Christian faith with an exclusionary breed of nationalism. (AP Photo/John Minchillo)

Braunstein said she isn’t sure what the future holds, but she’s particularly interested in the fate of conservative Christians who flee bastions of the religious right. She expressed particular interest in recent polling from PRRI indicating a sudden rise in white mainline Christians after years of decline. She said the shift needs more study but could indicate religious right exiles finding spiritual homes elsewhere — or at least identifying differently.

“We’re potentially seeing it on the ground in people who had disaffiliated from religion or leaving conservative Christian spaces, and are trying to create new spaces that are both religious and not necessarily in the vision of this politicized conservative religion that has become so prominent,” she said. “That’s taking lots of forms and requiring a lot of trial and error.”

This article originally appeared here.