WASHINGTON (RNS) — A religion scholar believes major trends in religion and politics can be traced back to the rise of the religious right in the 1990s, a sea change moment that set in motion an array of phenomena ranging from an uptick in religious disaffiliation to the radicalization of some Christian conservatives.

The sweeping theory is outlined in a new paper penned by Ruth Braunstein, an associate professor of sociology at the University of Connecticut. Her paper, titled “A Theory of Political Backlash: Assessing the Religious Right’s Effects on the Religious Field,” published late last year in Sociology of Religion, offers an unusually broad-based examination of the interplay between the religious right, the religiously unaffiliated and the power of political backlash.

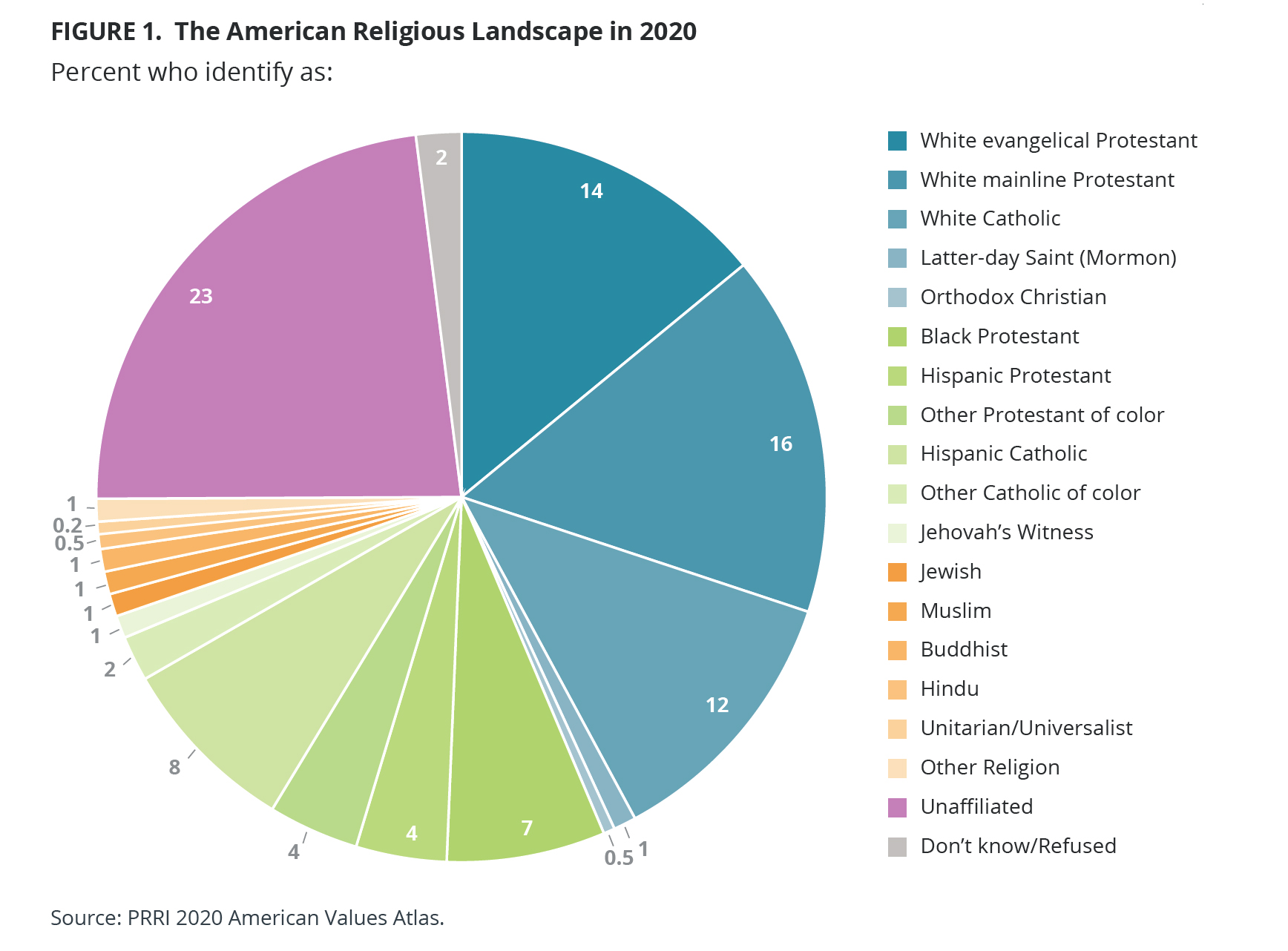

Braunstein grounds her study in a trend well known to scholars and everyday religious practitioners alike: The number of “nones,” so called because of the answer they give to the question “what is your religious affiliation,” has increased dramatically in recent decades. In 1972, the General Social Survey reported that 5% of Americans did not claim a religious affiliation. But that number shot up during the 1990s and again in the 2010s: According to the Public Religion Research Institute, the religiously unaffiliated represented around 23% of the country as of 2020 — a larger percentage than white evangelical Protestants, white mainline Protestants or white Catholics.

Graphic courtesy of PRRI Census of American Religion

Religious leaders and scholars have pondered the ongoing shift since it began, with some speculating the root cause is political. The rise of the nones, so the theory goes, is largely a backlash to the rise of the religious right in the 1990s: As campaigns by conservative Christians increasingly became associated with all religion in the public square, religious Americans who rejected their messages — particularly a subset of liberals with weaker connections to institutional religion — ultimately cut ties with religion altogether, identifying as nones instead.

But in her paper, Braunstein hypothesizes this cause-and-effect relationship is actually more complicated — and more wide-ranging. The uptick in liberal-leaning nones, she says, is but one example of “broad backlash” — a backlash against religion in general, even as some nones don’t necessarily give up religious practices or belief in a higher power. But, she argues, there are also at least three “narrow” backlashes to the religious right that have gone relatively unnoticed, all of which are helping shape the modern religious and political landscape.

“Backlash against the religious right doesn’t actually have to mean leaving religion altogether — even though that is a choice that many people are making,” she said in an interview this week with Religion News Service.

“There are some narrower forms of backlash that involve narrowly rejecting the religious right’s brand of politicized conservative religion by either reclaiming or reformulating a way of doing religion, of being religious and engaging in public religious expression.”

Ruth Braunstein. Photo courtesy of PRRI

Braunstein pointed to data from Pew Research showing an increase in Americans who identified as “spiritual but not religious,” rising from 19% in 2012 to 27% in 2017. In her paper, she acknowledged that while the category likely includes people who agree with the campaigns of the religious right, other scholars have studied people who claim the moniker as a reaction to the “moral lapses of organized religion,” signaling that at least some spiritual-but-not-religious Americans are “moderates, neither religious zealots nor dogmatic atheists” seeking to distance themselves from conservative Christians.

“It is plausible that the rising embrace of a spiritual identity can be read partially as a narrow backlash against the religious right, even as it also seems clear that it cannot be read exclusively in these terms,” writes Braunstein, who also heads the Meanings of Democracy Lab at the the University of Connecticut.

Second, she notes the growth in positive attention paid to liberal religious activists, sometimes described as members of the religious left, who are known for passionately decrying the political efforts of conservative Christians. Braunstein argues “progressive religious mobilization represents a different form of backlash than the one associated with religious disaffiliation,” one that doesn’t reject religion altogether but uses “the presence of the religious right to cast more moderate forms of public religious expression in a positive light.”