DURHAM, N.C. (RNS) — Three mornings a week, Susan Dunlap holds a half-hour prayer service for the overnight guests at Urban Ministries of Durham, a shelter for people without homes.

Unlike other shelters, some of which often require attendance at such services, there’s no sermon here, no order of worship, no hymnal.

The idea is to allow shelter residents to create a zone of belonging and recognition that is not controlled or scripted by others, she writes in her new book, “Shelter Theology: The Religious Lives of People without Homes.”

As an ordained Presbyterian with a Ph.D. in practical theology, Dunlap’s book is an attempt to provide anthropological study of what she has learned about the spiritual lives of the poor since she started the service in 2007.

Dunlap, who teaches the art of pastoral care at Duke Divinity School, spent countless hours with shelter guests and also taped interviews with those willing to offer their life testimonies. She wrote her book, she said, both to guide pastoral caregivers who venture into these spaces but also as a plea to other Christians to come closer to people on the margins. She quotes Bryan Stevenson, the founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, who once advised a group of graduates to “get proximate” to people who are suffering. “If you are willing to get closer to people who are suffering, you will find the power to change the world,” he said.

RNS spoke to Dunlap about her ministry, now held outdoors once a week due to COVID, and her book. The following interview was edited for length and clarity.

You write that, as a white clergy person, you hesitated for a long time before writing this book. How did you overcome that?

Susan Dunlap. Photo by Les Todd/Duke University

There are risks trying to represent people different from you, particularly if they’re very vulnerable. You risk violating them. It can be an act of violence. But it can also be an act of violence not to represent them. I thought to keep hidden what I learned about their insights and theology and lives was also wrong. My teacher, Mark Lewis Taylor, said these representations can be justified if you’re actively involved in changing the circumstances that victimize them. The whole time I’ve been working with them, I’ve been involved with Durham CAN (Congregations, Associations and Neighborhoods) to build affordable housing. That also justifies telling the stories of vulnerable people on the margins.

You refrain from calling the shelter’s guests homeless, for the most part. Is there a new style around that?

It’s become accepted to call them unhoused or people without homes. I prefer “people living without homes.” It’s a people-first language. I prefer saying they don’t have homes rather than saying they’re unhoused, because a home is a place of safety and nurture, more than just a house.

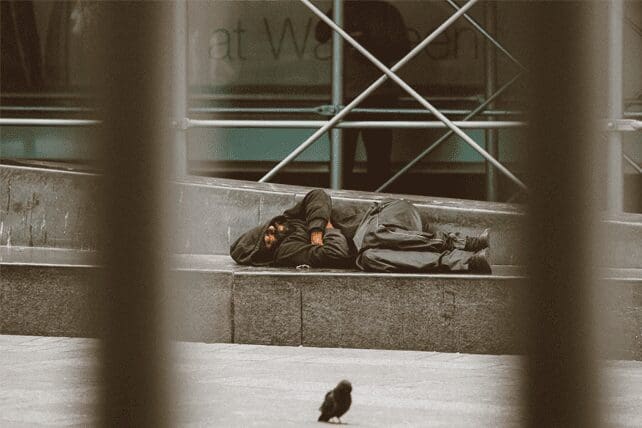

You talk about the horror of homelessness. Describe what you mean.

One of the things that symbolized that for me was walking down the street and one of my guides who lived at the shelter said, “That’s where Black people go for sex. That’s where white people go for sex. You see that pile of rocks? That’s a good place to hide for drug deals.” There’s a place under a railroad trestle where there was an old mattress, and he said, “That’s where you go to trade sex for drugs.” To me, that’s horror.

What did you have in mind when you created the prayer service and what did it become?

I had in mind creating a space that was not a place for my agenda, but theirs. They would walk into a quiet room and bring their own prayers to the front and light a candle, and meditative music would play in the background. It would be a place of nurture that affirms their connections to the divine. But they brought their religion with them, which is mostly Southern evangelical Black church. The music evolved from being instrumental to being gospel and organ music and singing. Rather than long spaces of silence, people gave testimony, they gave sermons, they encouraged each other, they praised God using common African American prayers like, “I thank God for waking me up this morning!” The music I felt was calming, they didn’t like. One woman told me, “It sounds like a funeral.”