She said it was a “big decision” to borrow money to continue the education she felt God called her to pursue.

“But honestly, it came down to my mental and emotional health,” she said.

Many students and grads, like Judd, are at least bivocational.

The Rev. Lawrence Ganzy Jr. is in his fourth year at Hood Theological Seminary, where he attends a track that allows him to pastor an African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in South Carolina while taking classes on Friday nights and Saturdays. During the week, he’s an admissions officer for Strayer University.

Prior to seminary, his work through the Carolina College Advising Corps, a government program for University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill graduates to counsel low-income high school students, helped him afford the start of his theological studies.

“That paid for my first year of seminary,” said Ganzy, 26. “Then when I got to the next year, that money was gone.”

Keynoting the opening night of the collaborative meeting, the Rev. Michael Brown, president of Payne Theological Seminary in Wilberforce, Ohio, pointed to the portion of the Lord’s Prayer that says “forgive us our debts as we forgive those who are indebted to us” in the Gospel of Matthew.

“Debt keeps us chained to the past and it doesn’t open up possibilities for the future,” he said, “and so the idea of the forgiveness of debt in the Lord’s Prayer is that it releases you to do things for God.”

During the event, graduates spoke of the additional financial struggles they faced, such as debt affecting their credit scores as they try to purchase a car and escalating rent, sometimes in historically Black neighborhoods that have been gentrified.

Brisbon pointed out that Black theological schools may have small endowments and may not get support from their alumni, in part because of the often-lower salaries received by their graduates.

“Black preachers may love their school as much as somebody else but they can’t give money that they don’t have,” she said.

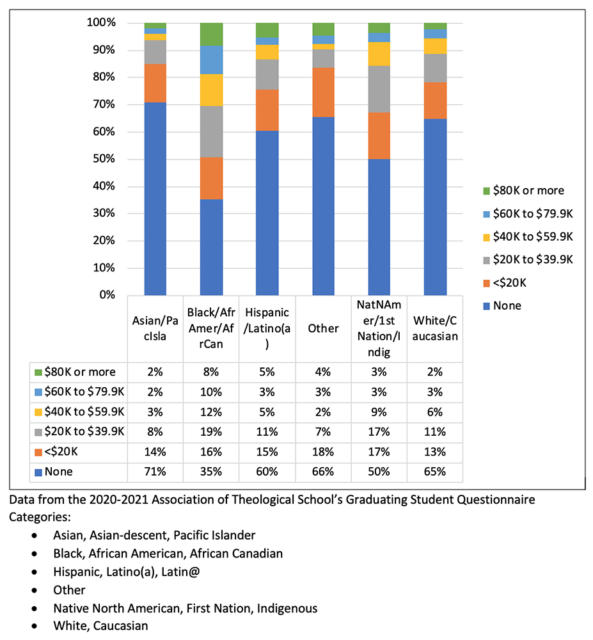

The ATS report noted that a 2003 Pulpit & Pew study found that, on average, Black clergy salaries were about two-thirds those of white clergy. In a 2019 Christian Century essay, scholars noted that a study by the Samuel DeWitt Proctor Conference found that one-third of Black pastors believed they were “fairly and adequately compensated as a professional” while 67% said that they had “particular financial stress” at that current time.

The Rev. Leo Whitaker, executive minister of the Baptist General Convention of Virginia, told Religion News Service that some clergy in the more than 1,000 churches in his Black state denomination are often “bivocational if not trivocational” to make ends meet, especially when they are located in a region like the state’s Northern Neck rather than the city of Richmond.

Whitaker suggested to collaborative members that they look to U.S. government programs that offer debt forgiveness to educators and doctors who serve in needy communities, noting they should offer the same for seminary grads. He hopes collaborative members will discuss his idea with seminary and education officials.

“You’re serving a stressed community and you’re financially stressed yourself without the ability to make the necessary funds and it’s not about them having a choice of where they choose to serve,” he said, noting that Methodist bishops appoint clergy and Baptist clergy go where congregations have called them to serve. “In ministry our location is not always assigned to us by choice.”