(RNS ) — “God told me to pray for you!” is about the last thing Amy Kenny wants to hear when she cruises into church riding Diana, the mobility scooter she has named after Wonder Woman.

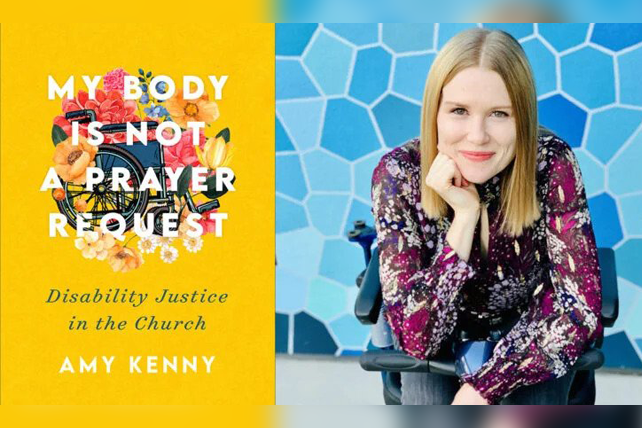

It’s not that she has anything against prayer. Kenny, a Shakespeare scholar and lecturer at the University of California, Riverside who is disabled, would simply like other Christians to quit treating her body as defective. “To suggest that I am anything less than sanctified and redeemed is to suppress the image of God in my disabled body and to limit how God is already at work through my life,” Kenny writes in her new book, “My Body Is Not a Prayer Request.”

The book, which comes out this month, invites readers to consider how ableism is baked into their everyday assumptions and imagines a world — and a church — where the needs of disabled people aren’t ignored or tolerated, but are given their rightful place at the center of conversations.

Kenny combines humor and personal anecdotes with biblical reflections to show how disabilities, far from being a failure of nature or the Divine, point to God’s vastness. She reframes often overlooked stories about disability in Scripture, from Jacob’s limp to Jesus’ post-crucifixion scars. Abolishing ableism, she concludes, benefits disabled and nondisabled people alike.

Religion News Service spoke to Kenny about making the church what she calls a “crip space,” her belief in a disabled God and why she prefers Good Friday over Easter. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

At what point did you begin seeing your disability as a blessing?

I was told often by doctors that my spine and my leg and my body was crooked. I began seeing how crooked and jagged creation is, the way elm trees have snaking branches and maple leaves are ragged and kangaroos don’t walk but hop. I didn’t have any trouble thinking about those elements as beautiful and divine. Yet when applied to humans, disability was thought of as dangerous and sinful. That just didn’t make sense to me. So based on the idea that creation is delightfully crooked, I started to think about how my body, too, is made in the image of the Divine and its crookedness isn’t anything to be ashamed of.

Can you explain the difference between curing and healing?

I think of curing as a physical process, usually a pretty rapid one — in Western society, going to the doctor and wanting a fix for whatever illness you are experiencing. Healing is much richer than that. It’s deeper. Healing is messy and complex. It takes time. It’s about restoring someone to communal wellness.

What is “crip space” and what does it look like in the context of a church?

Crip space is a disability community term that is reclaiming what has been used as a derogatory slur against us, cripple, as a way of gaining disability pride. It’s saying that we are not ashamed to be disabled, that our body-minds are not embarrassments. Crip space puts those who are most marginalized at the center and follows their lead. So folks who are queer, black, disabled people.

Generally, churches want a checklist or a list of don’ts. It’s much more nuanced and human than that. It’s noticing that there’s no ramp to the building you’re in, or no sensory spaces for people to take a break. It’s noticing that the language of the songs or the sermon is ableist and changing those words. It’s recognizing when the community is missing disabled folks. I’ve often had that as an excuse: “We don’t have any other disabled people but you.” Well, I wonder if that’s related to your lack of accessibility.

Could you share why you use the term body-minds?

It’s a disability community term that is attempting to undo some of that mind/body dualism. And it’s asking for us to think about how our bodies and our minds work in concert with one another. It’s also a way of being inclusive, making sure that when we talk about disability, we’re not just talking about mobility issues. We’re not just talking about visible disabilities. We’re also talking about hidden disabilities.