ADVANCE, N.C. (RNS) — The new church meets in what used to be a dog kennel.

A floor drain in the middle of the worship area is a reminder of its former use. But over the past few months one of the two metal garage doors was replaced with large glass windows. The concrete floor has been refinished, the walls repainted, curtains hung, the bathrooms renovated.

Here, in the middle of a bland industrial park that looks like a self-storage facility, a new church is emerging.

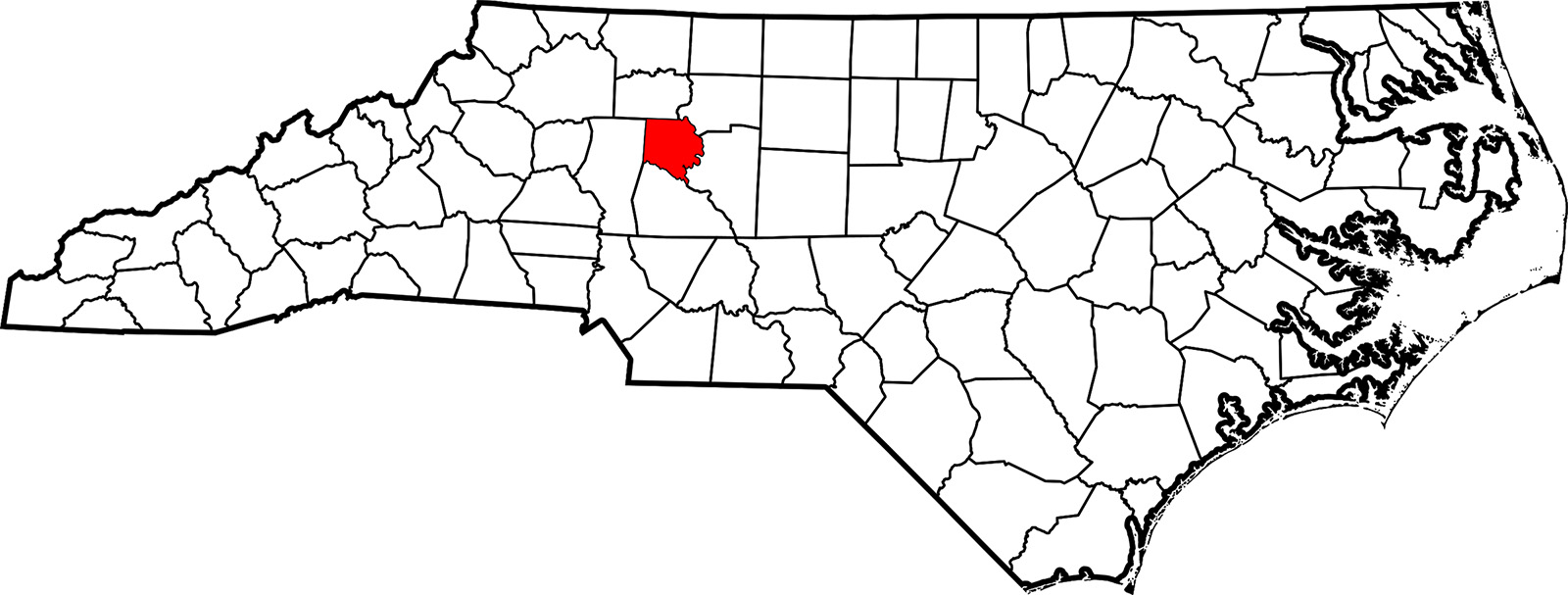

Its 40-plus members think of themselves as “the remnant.” For years, they belonged to various United Methodist churches in Davie County, North Carolina. But over the past four years, a majority of the county’s 24 United Methodist churches voted to disaffiliate from the denomination. Only 11 remain, most of them on the outskirts of this rural county located in the state’s Piedmont region, about 65 miles north of Charlotte.

RELATED: United Methodist Pastors Feel Worse and Worry More Than a Decade Ago

The members of Grace United Methodist Mission — they are not formally a church yet — were blindsided by their different congregations’ sudden push to sever ties with the denomination they had grown up in and worshipped with their entire lives. They came together as a group like refugees often do, with one thing in common — a profound grief at losing their church home and a resolve to remain United Methodist.

“We were broken when we came here — I’m telling you we all were broken!” said Lois Steelman, formerly of Bethlehem United Methodist Church. That church, a few miles down the road, had a heritage stretching back to John Wesley, the 18th-century founder of Methodism. Steelman and her husband Joe were members for 50 years.

But under the leadership of the Rev. Suzanne Michael, an enterprising United Methodist pastor with a Dolly Parton-like accent and blond hair to match, these remnant United Methodists are trying something new.

They want to complete the renovation of their rental space, especially to add a small children’s play area. But they have no desire to buy land or build a church. In the pioneering spirit of the early Methodists, the members of Grace want to keep things simple.

“All they wanted was a place to meet to start serving the world,” said Michael, who serves as the emerging community pastor for Davie County in addition to leading Grace.

In the past five years, more than 7,600 churches have cut their ties to the United Methodist Church, the nation’s second-largest Protestant denomination — about 25% of its 30,000 churches have broken away. That five-year window that allowed churches to leave with their properties ends this month, and the denomination’s legislative arm will meet in Charlotte in April to chart a new way forward for those that remain.

Davie County, red, in North Carolina. (Map courtesy Wikipedia/Creative Commons)

In the Western North Carolina Conference of the United Methodist Church, a region that spans the 47 Western counties, the vast majority of the churches that broke away were small and rural, politically and theologically conservative.

They did not want to see the denomination loosen its rules to allow the ordination and marriage of LGBTQ people. And many were wary of seemingly far-away institutions that required annual apportionments to fund the work of the denomination around the world.

“It’s hard to be a connectional church when there’s a culture that focuses on the local,” said Bishop Ken Carter of the Western North Carolina Conference.