Even some gay Catholics saw the pope’s move as too abrupt. “Heavy-handed papal interventions won’t work and are even likely to harden resistance,” observed Catholic theologian Lisa Sowle Cahill in an essay published on Monday (Jan. 22) in Outreach, a Catholic magazine focused on LGBTQ inclusion in the church.

Becquart insisted that even the controversy over blessing same-sex individuals is an example of synodality working. “The fact that people react, including bishops and bishop’s conferences, is a fruit of the synod in a way,” she said, adding that Ambongo quoted from the synodal documents in his statement and called for an open consultation with all African bishops on the matter.

“Many decisions are up to the pope, but it doesn’t mean that you don’t reflect, discern and propose to him,” Becquart said.

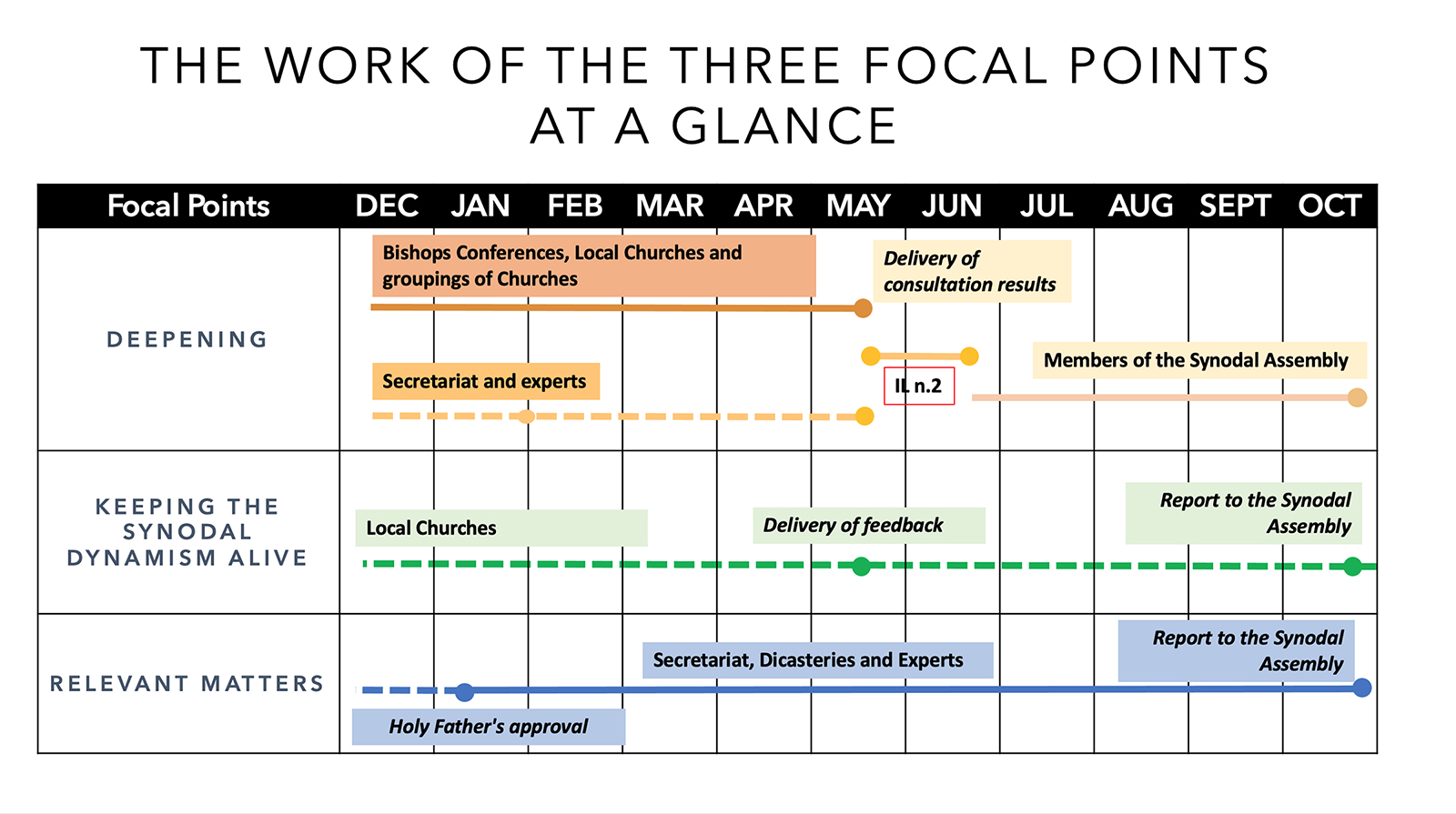

In February, at a meeting of the Synod council, Francis will be presented with a list of topics that require further reflection, including women deacons, the formation of priests and proposed reforms to the church’s catechism. He will then appoint experts and theologians to collaborate with the Vatican’s curial offices on a report to be submitted in time for the synod’s second session.

A timeline of the 2024 synodal process focal points. (Courtesy image)

Meanwhile, time is short for the organizers to gather feedback from local churches in time for the next assembly. In a worksheet issued to help local churches reflect on the results from the first session, synod organizers suggest picking three priorities and initiatives to focus on. The document also encourages local communities to submit a sample of their reflections to a local committee of theologians, canonists and pastoral leaders.

Each country’s bishops’ conference is charged with overseeing this process and drafting a summary of no more than eight pages, to be sent to the Vatican’s Synod office by May 15.

“We are aware of the question of time,” Becquart said, “but from the beginning we also emphasized that it’s not just about being a good student and sending documents and books. The most important thing is how you continue in this synodal process.”

Becquart said that it’s up to local dioceses to figure out ways to widen participation, particularly among those who have drifted away from the church or live on the margins. “If you look at just the numbers of those who participated, we are far from all the baptized,” Becquart said, “but synodality is step by step.”

Sister Nathalie Becquart speaks at St. Paul the Apostle Church in Manhattan, Tuesday, March 28, 2023, as part of Fordham University’s annual Russo Lecture series. (Photo by Leo Sorel Photography/Fordham University)

A new Instrumentum Laboris summarizing all these deliberations is expected to be published between June and July, “a first possible draft,” Becquart said, for synod members to discuss and amend.

There are plenty of other tasks on Becquart’s to-do list. A major takeaway from the first assembly last fall was the need for theologians and canon lawyers in the synod hall to address questions in real time, Becquart said. Another unresolved question is media access: Francis, looking to promote a free exchange of ideas, issued a gag order on participants until after the synod.

Despite the challenges, Becquart pointed to numerous initiatives that show how synodality is being adopted in concrete ways. In Africa, there are synodal schools and in Switzerland synodal church structures. Catholic educators and religious orders are developing resources and trainings on synodality. Those who attended the first synod “lit a fire” of synodality in their local churches all over the world, she said.

“If you look at the beginning of the synod, where we were and where we are now, synodality is an important topic and reality,” Becquart said. “Not to say that it’s perfect everywhere, we know there are resistances. But I see that something big is going on, even though it doesn’t make a lot of noise.”

This article originally appeared here.