PHILADELPHIA (RNS) — Surrounded by the soaring ceilings and stained glass of Christ Community Church, the gathering looked like a typical worship service. Speakers taught and testified as the 100 or so attendees prayed and nodded along.

But the event, which took place in early January, was aimed not at praise but at raising awareness among Christians about how their communities can better welcome and look out for those who suffer from mental illness. After an opening song, the group settled in for a panel and Q&A titled “It’s a Family Affair: Exploring the Intersection of Mental Health, Spirituality and Faith.”

It was hosted by the American Psychiatric Association in partnership with the Christian Mental Health Initiative and the church.

RELATED: Why Mental Health and Spiritual Health Must Go Hand in Hand

“I would love to see more of this in churches,” said Christian Mackey, a college student considering a mental health career. “I think it was really helpful getting the combination of spirituality and mental health. … There’s more than just prayer; there are other options available.”

Long a taboo topic in religious circles — whether clergy burning out on ministry or laypeople turning to faith communities for help — mental health has become a topic too prevalent to avoid inside many faith communities, while local and national outside initiatives have recognized that houses of worship have a nearly unique ability to reach underserved communities.

One such latter enterprise is the Christian Mental Health Initiative, a nonprofit that takes free mental health trainings into churches, especially primarily Black churches like Christ Community.

Dr. Atasha Jordan, center, poses with colleagues during the community roundtable, “It’s a Family Affair: Exploring the Intersection of Mental Health, Spirituality and Faith,” at Christ Community Church of Philadelphia, on Jan. 4, 2025. (Photo courtesy of Christian Mental Health Initiative)

At the January event, CMHI founder Dr. Atasha Jordan, a psychiatrist at Cooper University Health Care in Camden, New Jersey, wore a top that said “JESUS + THERAPY.”

“Before I’m a doctor, before being a nonprofit founder, I’m a daughter,” said Jordan, who stressed that community is an important value in mental health, as in faith. “I was born in Barbados. I’m a wife. … I am a sister.”

Cheryssa Hislop, a second-year medical student at the University of Pennsylvania and volunteer with CMHI, said: “Sometimes people embark on this journey of medicine and forget why they started, or forget where they came from. It’s just so inspiring to me that Dr. Jordan clearly not only remembers where she came from, but tries to honor it by giving back.”

In her close-knit Christian family, mental health wasn’t a frequent topic of conversation, said Jordan, who faced mental health challenges while in college at Harvard University and, later, in medical school at the University of Pennsylvania. As her awareness of mental health grew, so did her understanding that Christianity and therapy could coexist.

The connection truly clicked, she said, on the first day of her psychiatry rotation as a medical student. At the Veterans Hospital in Philadelphia, Jordan watched as patients shared how the care they’d received inspired hope.

“That was a very spiritual moment for me,” said Jordan.

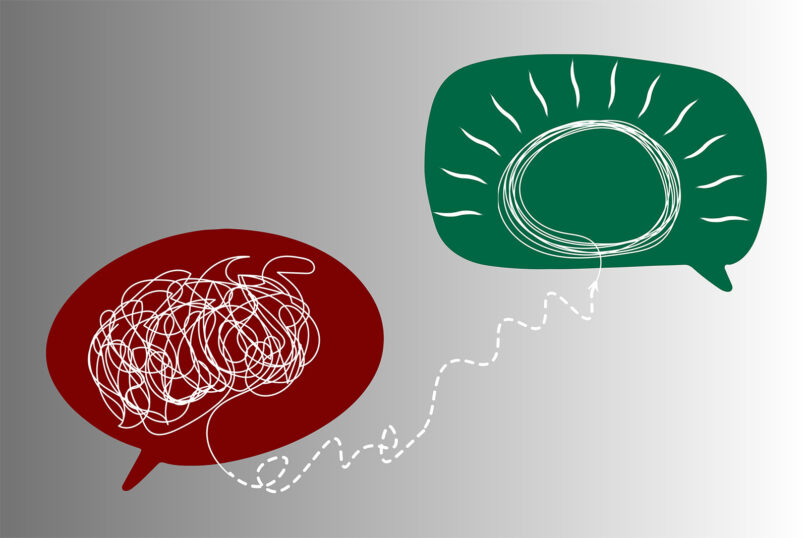

(Image by Rosy/Bad Homburg/Pixabay/Creative Commons)

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Jordan, still a medical resident, was invited by a Philadelphia church to speak about depression. She was struck by the number of people who attended, which laid bare the hunger in the church at large for informed discussions about mental health.

Around the same time, Jordan said, she received what she described as “a very clear word from God” to start CMHI — “like it was downloaded” to her mind, she said.

“Mental illness is a real thing, like diabetes, like cancer or like high blood pressure, that can be treated and is not a derogatory term,” Jordan said about CMHI’s message. “We bring down the stigma, so that people can say ‘I’m a Christian and I can experience mental illness, and it says nothing about my faith if I reach out for support from a therapist or from a psychiatrist.’”

Her first step was to gather data to assess the needs of the local faith community. With the help of a fellowship and $25,000 grant through the American Psychiatric Association Foundation and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Jordan conducted a pilot study on the use of mental health first aid — a type of training that equips laypeople to recognize warning signs of mental illness, effectively intervene and provide access to professional help — in Black churches across Philadelphia.