“I think we mistakenly withdrew from our traditional Black churches, thinking that we had something better and later discovered that we didn’t have anything better,” he said. “We may have had something a little different but it wasn’t better.”

Despite the challenges — where their concerns went unheard and sometimes people refused to sit next to them — some felt a sense of calling to be the first and only Black staffers or leaders in predominantly white institutions.

Ruth Lewis Bentley is interviewed in the “Black + Evangelical” documentary. (Courtesy photo)

“I went through some difficult times at Wheaton, on the board, trying to follow their lead,” said Ruth Lewis Bentley, a co-founder of the National Black Evangelical Association and the first Black woman to serve on Wheaton’s trustee board and the staff of InterVarsity Christian Fellowship, in the documentary. “And maybe the Lord doesn’t call everybody to help people in this respect. But I felt the Lord called me to be an instrument.”

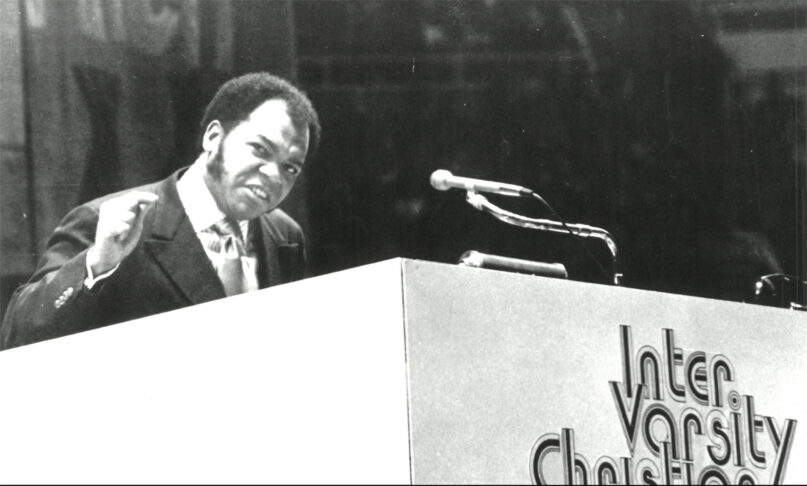

The turning point for many Black evangelicals was a rousing 1970 sermon by Skinner at the IVCF’s triennial Urbana conference. “Any gospel that doesn’t want to go where people are hungry, and people are poverty stricken and set them free in the name of Jesus Christ is not the gospel,” he preached, drawing the interracial audience to its feet.

Both Bacote and historian Jemar Tisby, who is interviewed in the documentary, called it “an awakening moment,” with Tisby saying it prompted white people in the audience to know “racial progress had to be part of what it meant to be a Christian in the United States.”

But the cheers faded, as Black evangelicals were again dismissed. E. Brandt Gustavson, then-broadcasting director of the Moody Bible Institute’s radio network, dropped Skinner for being “increasingly political” on his show. (Gustavson would later become the president of the National Religious Broadcasters.)

Tom Skinner preaches at InterVarsity Christian Fellowship’s Urbana 1970 conference at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, as featured in the “Black + Evangelical” documentary. (Courtesy photo)

Bacote told RNS that the arc of Skinner’s story is one experienced by other Black evangelicals, from “Oh, hey, you’re great, you’re talented” to “Why are you getting political?”

He offered the Christian hip-hop artist Lecrae as a more recent example. “When he wrote (that) he wasn’t sure about the term evangelical,” Bacote recalled, “people were mad about him saying that. Well, this is not the first person to be thinking this.”

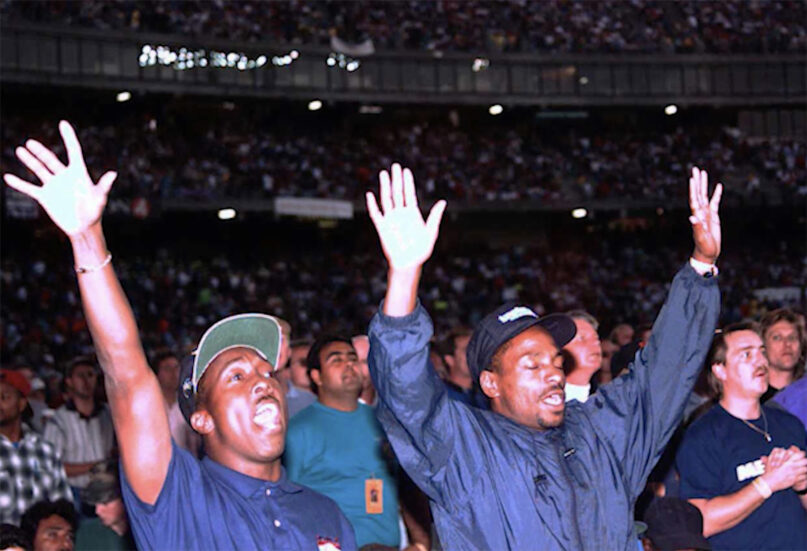

In the 1990s, former University of Colorado coach Bill McCartney attempted to make his Promise Keepers movement a model of racial reconciliation, but his effort, too, soon became a point of criticism.

“What could have happened was those moments could have had a ripple effect to impact the institutions of evangelicalism,” said Nicole Martin, COO of Christianity Today, in an interview near the end of the film. “What did happen was an understanding of the cost and, from my vantage point, an unwillingness to pay that cost.”

The documentary’s premiere, attended by about 275 students, community members and people featured in the film, was preceded earlier in the month by a webinar co-hosted by the National Association of Evangelicals, which in recent years has hosted spiritual retreats for leaders of color and is planning a third one in the fall.

A Promise Keepers event highlighted in the “Black + Evangelical” documentary. (Courtesy photo)

“This retreat has been a great support for people of color who are serving in predominantly white spaces,” Mekdes Haddis, project director for the NAE’s Racial Justice and Reconciliation Collaborative, told RNS via email. “Many have been leading racial reconciliation and justice efforts, without a lot of support.”

The premiere of the documentary, which Bacote had long planned for Black History Month, took place as Wheaton was dealing with backlash for its congratulatory message for alumnus and White House official Russell Vought that drew competing letters from alumni about its politics. One letter accused the college of upholding a “DEI regime.” However, Bacote said he had not received pushback about the screening.

Instead, he has received requests for additional screenings and plans to post the documentary online by April.

At the end of the documentary, Bacote concludes there are more people than he realized living out the tensions of being Black and evangelical. “Too often I thought I was standing at these crossroads by myself,” he said. “But over the years I have discovered I am far from alone.”

This article originally appeared here.