(RNS) — For decades, Stanley Carlson-Thies has worked to demystify the “faith-based office” that has been part of the White House during the last five presidential administrations.

The founder of the Institutional Religious Freedom Alliance also has worked to defend faith-based organizations, making sure they, along with secular groups, are heard and supported by governments and given an equal chance at funding for the social services they provide.

“It’s not a theocracy; there’s no automatic money going to religious groups,” Carlson-Thies said in an interview days before his retirement party at Washington’s Museum of the Bible. “If you read the regulations, it says they can’t get it just because they’re religious, or they can’t be turned away just because they’re religious.”

After working in the first White House Office of Faith-Based and Community Initiatives, he initially started the IRFA as an independent organization in 2008. It now is part of the Center for Public Justice, a nonpartisan organization headquartered in Alexandria, Virginia, and focused on policy research, where Carlson-Thies worked before he started IRFA and since the alliance came under the center’s umbrella.

As of his Wednesday (April 30) retirement, Carlson-Thies will continue as a CPJ fellow and consultant.

Carlson-Thies, 75, was born in Tokyo to missionary parents and describes himself as a Reformed Christian Calvinist and a “centrist conservative.” He has also taught Sunday school at his Presbyterian Church in America-affiliated congregation in Maryland.

Looking toward retirement, he talked with RNS about what the White House faith-based office has accomplished, how it has been misunderstood and what he hopes for its future.

The interview was edited for length and clarity.

Why did you found the IRFA?

Often conceptually what springs to mind is individual religious freedom, which is critical. But one way communities and people of faith live out their faith is through institutions. And although that was always part of what was going on in government regulations and in law cases, it seemed to me that there needed to be a more definite focus on exactly what are those institutions. What do they need so they can do the things they can best do?

And those institutions aren’t just houses of worship.

No, no. Houses of worship, of course, are part of them, but there are hundreds of thousands of faith-based nonprofits separately from worship, but they still do their things because of faith and in a way are structured by the faith.

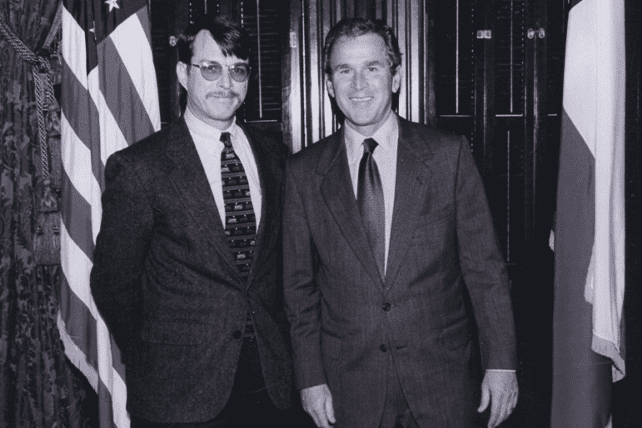

You worked under John DiIulio in George W. Bush’s administration, in the first White House Office of Faith-Based and Community Initiatives that opened in 2001. What do you consider that office’s greatest achievement?

I think the most important achievement was to put in the consciousness of the federal government how important faith-based and secular organizations are in what they do for society, both separately from government and in partnership.

Barry Lynn, who led Americans United for Separation of Church and State for a long time, called the White House faith-based initiative “a mess.” How did the office overcome the criticisms of church-state separationists over the years?

I think it was what actually was done. My guess is a lot of people — maybe not Barry Lynn — thought that what happened wasn’t quite what they feared. And to me, that probably explains why the George W. Bush faith-based initiative was continued by Barack Obama right after there was a lot of suspicion and worry. But I think the worries turned out not to be the case, partly because there was a lot of dialogue back and forth about what’s unconstitutional, what’s unfair.