CHARLOTTE, N.C. (RNS) — Four years ago, the Rev. Matt Conner presented his congregation with a stark reality: Newell Presbyterian Church had about 18 months of financial solvency ahead. The time had come to seriously consider its future.

Chartered in 1890 in what was then a sleepy part of northeast Charlotte dotted with dairy farms and tobacco fields, the church grew, and then started a slow decline. These days about 50 people attend Sunday morning services and the church has an annual budget of $190,000.

But Newell Presbyterian has one asset increasingly in demand in the now bustling neighborhood of subdivisions and apartment complexes: land. The church sits on 9.5 acres, accumulated plot by plot by devoted church members who had long since passed on.

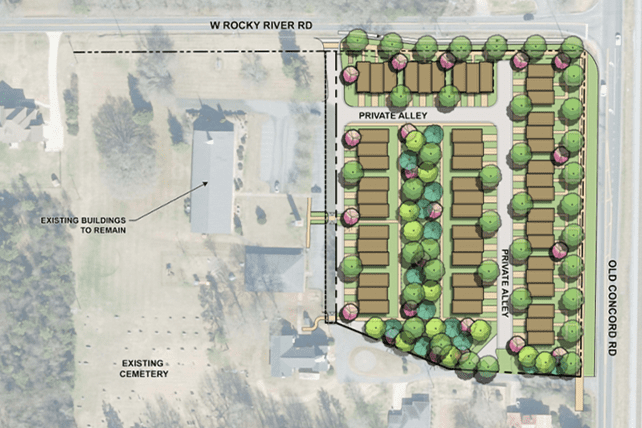

After forming a “dream team” to consider its options, the church recently voted to sell a 4.5-acre parcel to a nonprofit developer for the construction of 50 affordable townhomes right next to its sanctuary. Homeowners would have to earn 80% of the area median income (about $85,000 for a family of four) to qualify. The sale is expected to be inked in October.

Newell Presbyterian is one of hundreds of declining congregations with underutilized space, excess land, deteriorating buildings and soaring maintenance costs. But these churches are finding that they can stanch their fiscal woes by selling or, in many cases, leasing some of their land and repurposing their properties for affordable housing.

At least 200 and as many as 400 houses of worship (mostly churches but also synagogues and mosques) have repurposed their property for affordable housing over the past decade, said Nadia Mian, a researcher at Rutgers University’s Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy who is cataloging those projects.

Newell Presbyterian Church in Charlotte, N.C. (RNS photo/Yonat Shimron)

Newell Presbyterian found that in selling its land it had found a new treasure: its soul.

“I’ve gotten to watch and be a part of a kind of spiritual growth in this space and time and a calling to be even more mission oriented,” said Conner. “This is a church getting clearer about who we are and why we exist.”

Though the church hasn’t grown in numbers, Conner said it has grown in faith and commitment, and its members speak of a renewed sense of purpose and mission, a deeper spirituality rooted in a sacred responsibility to neighbor and place.

In 2021, on the Feast of Ascension, when Christians celebrate the resurrected Jesus’ leavetaking of his disciples, Conner asked a group of church elders to walk the grassy 4.5-acre field next to the church. “Pray, pay attention and dream,” he told them. “What do you see?”