(RNS) — It’s no secret America’s youth are in crisis.

Born into a tech-saturated world shaken by domestic terrorism, ecological devastation and economic instability, Gen-Zers are more likely to report mental health concerns like anxiety and depression than older generations. In many ways, the pandemic has forced mental health discourse into the limelight, prompting the U.S. surgeon general to issue an advisory last December on COVID-19’s “devastating” impact on youth mental health.

A new study of 13–25-year-olds, from Springtide Research Institute, suggests spirituality could be part of the remedy — though for some young people, it also contributes to the problem.

“I think religion … is a place to find belonging. It’s a place to connect with a higher purpose, which is a calling from God in my understanding,” said Mark, 22, an interviewee cited in the report. “I think it’s also, for many people, a restriction of freedom and sort of obligation, which creates a lot of shame in people’s lives.”

In general, the report — which is based on qualitative interviews as well as fielded surveys — finds that having religious/spiritual beliefs, identities, practices and communities are all correlated with better mental wellness among youth.

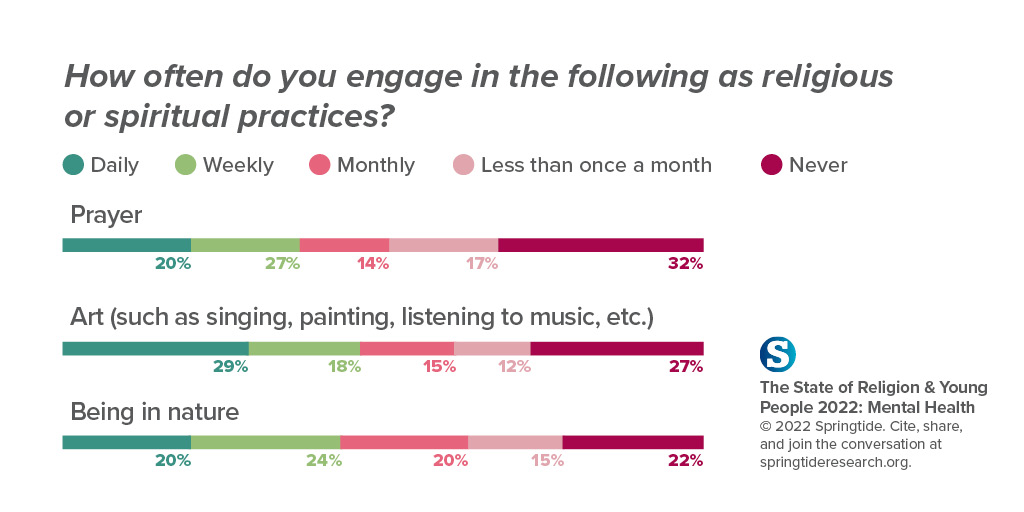

A majority of all young people (57%) and nearly three-quarters of religious young people (73%) surveyed agree their religious or spiritual practices positively impact their mental health. Many participants cite prayer as playing a role in their spiritual practice — 51% said they started praying regularly during the pandemic — and 74% of participants who pray daily say they are flourishing, compared to 57% who never pray.

“How often do you engage in the following as religious or spiritual practices?” Graphic courtesy of Springtide Research

Spiritual beliefs and community identity also correlate with positive mental health. Seventy-four percent of young people who identify as “very religious” say they agree or strongly agree that they are “in good physical and emotional condition,” compared to 42% of non-religious young people. Seven in 10 young people (70%) currently connected to a spiritual or religious community report having “discovered a satisfying life purpose,” as compared to 55% of those who used to be connected to such a community.

Forty-two percent of those who feel highly connected to a higher power report they are “flourishing a lot” in their emotional and mental health, compared to 16% of those who say they do not feel at all connected to a higher power.

Still, findings are complex — 27% of religiously affiliated youth say they are “flourishing a lot,” but 28% also say they are “not flourishing,” a finding that suggests simply being affiliated with a religion is not a mental health cure-all.

In interviews, participants also spoke about how religion can negatively impact their mental health.

“(Y)oung people make it clear that religion feels toxic when it is primarily presented as a pressure to live up to difficult expectations, rather than a vehicle for helping them navigate their current difficulties,” the report says.