(RNS) — Sister Wendy Beckett was both a contemplative, deeply devoted to a life of prayer, and also, improbably, a BBC star, and later the subject of a British musical.

For years, Beckett had lived as a hermit in a trailer on the grounds of the Quidenham Carmelite Monastery in England. Then, beginning at age 61, she soared to international stardom with a series of BBC documentaries in which she toured museums across the world in her billowy black nun’s habit, speaking about art with awe and wonder and showing people how to appreciate it.

In the years before her death in 2018, she began a three-year correspondence with Robert Ellsberg, the publisher and editor in chief of Orbis Books, an imprint of the Maryknoll order. Earlier in life, Ellsberg had been the managing editor of the “Catholic Worker” and spent five years assisting the movement’s founder, Dorothy Day, whom Beckett much admired.

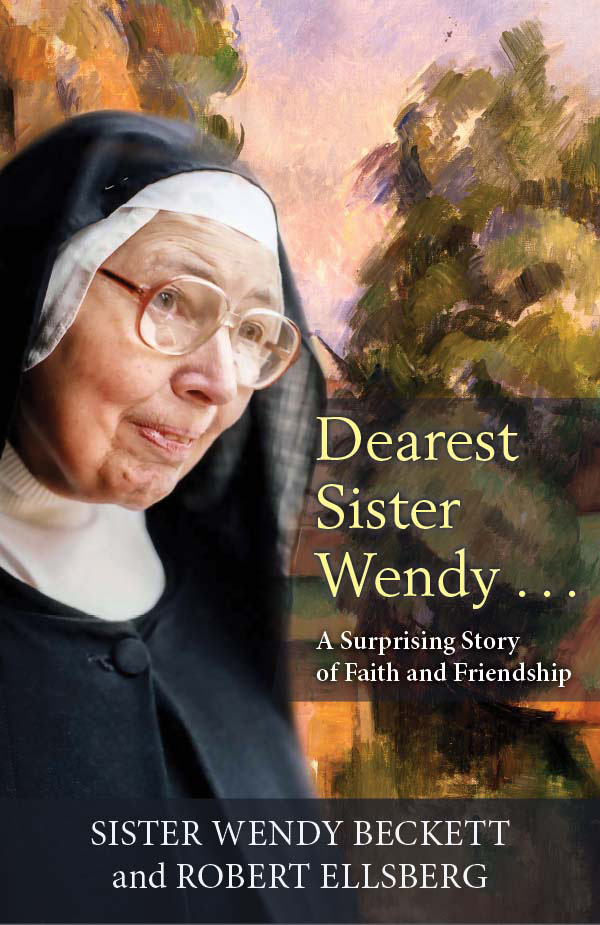

Ellsberg has now published a collection of his near-daily correspondence with Beckett, “Dearest Sister Wendy… A Surprising Story of Faith and Friendship.” The book includes three years’ worth of emailed letters back and forth on such subjects as saints, holiness, beauty, suffering and prayer.

RNS spoke to Ellsberg about Beckett, who combined a fierce intellectual capacity with a zealous devotion to Jesus and a growing willingness to open up about her life. The following interview was edited for length and clarity.

How did this correspondence come about?

Sister Wendy sent me a note asking if we had damaged copies of an expensive series of books on Vatican II that we might donate to the monastery where she lived. After that we exchanged notes from time to time. But her handwriting (made it) so hard to read her letters that it didn’t encourage prolonged correspondence. When she was too old and infirm to live in her trailer, Sister Wendy began dictating letters to Sister Lesley Lockwood. That meant it was possible to have completely legible messages from Sister Wendy.

Sister Wendy took very seriously her life as a contemplative and minimized all contact with the outside world. Why do you think she wanted to correspond with you?

“Dearest Sister Wendy… A Surprising Story of Faith and Friendship” by Sister Wendy Beckett and Robert Ellsberg. Courtesy image

I piqued her interest in things that were of infinite interest to her — saints, spiritual masters, holiness. Early on, I said, ‘I would love it if you would write about your personal life, your life of prayer or your own spiritual journey.’ She didn’t have any interest. But at some point, we did venture into personal things, I think partly prompted by sharing my own story. I would describe things that happened to me and ask what she thought of it. She would respond to what I shared and shared more about herself. A kind of trust emerged between us. We realized we were creating something together. She knew her life expectancy was short. It put her in mind to reflect on things.

Why were saints so important to Sister Wendy?

The veneration of saints goes back to the early Christian church. Originally it was martyrs. Then it was realized there were other ways of laying down your life through prayer, service and dedication. The church recognized people who were emblems of the holiness of God. They were not perfect but achieved a distinction in their spiritual life that would inspire others. Sister Wendy was interested in those exemplary figures who serve as special inspiration and models and the everyday holiness we’re called to. She was also interested in people who may not be officially canonized as saints but whose questing and longing for God may inspire others.

You worked for one of those who may one day be declared a saint: Dorothy Day. How did that come about?

I had taken a year’s leave of absence from college when I was 19. I had been raised as an Episcopalian but was inspired by Gandhi. That’s what drew me to the Catholic Worker. It reflected the Gandhian approach to nonviolence, living in community, valuing common work and the works of mercy, protesting against structures that gave rise to poverty. I wrote articles about Gandhi for the Catholic Worker (newspaper), which Dorothy Day liked very much. She asked me if I would edit the Catholic Worker when I was 20.

I ended up remaining at the Catholic Worker for five years. It grounded my values and sense of myself in the Catholic Church, and I was ultimately received in the church in 1980. Dorothy Day died soon after that, and I immediately began editing her selected writings that were published later. I spent many of the decades since she died reflecting on her life and promoting her legacy, and that has involved promoting her cause for canonization.

Sister Wendy wrote that she would go to bed at 6 p.m., get up at 11:30 p.m. and pray all night long. What kind of order is that?

Sister Wendy lived on the grounds of the Carmelite order but she was not a member of it. She had taken private vows as a consecrated virgin and hermit. As a hermit, she considered her whole life prayer. She would be in the darkness of her cell and pray. It was a total silence, sitting there in the presence of God, opening her mind and heart to the love of God. In the morning she went to Mass. Then she spent the morning reading or looking at pictures of art, which for her was a contemplative practice. She considered all things referred her to God.