(RNS) — If a member of the clergy suspects a child in the congregation has been abused, is the clergyperson legally required to report it?

In New York state, the answer is no. But some advocates, clergy and lawmakers think that should change.

This issue is at the heart the Child Abuse Reporting Expansion Act, a bill making its way through New York state Legislature that, if passed, would make clergy mandated reporters.

“CFCtoo is calling for CARE Act to be passed because we see it as a necessary first step toward making our communities and children safer,” said anti-abuse advocate Abbi Nye.

Nye is part of the advocacy group CFCtoo, a collective of former Christian Fellowship Center members. The CFC has five locations in New York’s North Country and has been described by some former members as insular. CFCtoo formed in June 2022 after congregation member Sean Ferguson was charged with having sexually abused his two young daughters in 2015. Church members later learned that leaders knew about the abuse years prior but did not report it to authorities or to the broader church community.

RELATED: SBC Sexual Abuse Survivor Tiffany Thigpen: The Four Pastors Have Done Johnny Hunt ‘A Disservice’

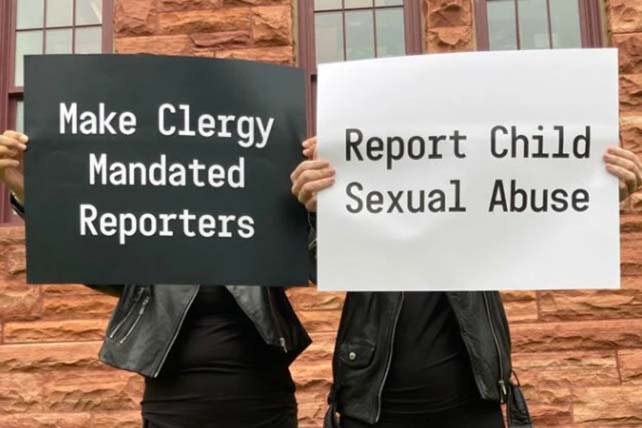

In October, CFCtoo held a press conference outside of the St. Lawrence County Courthouse to advocate for the CARE Act.

“We are aware of a number of cases, most recently with Sean Ferguson, where CFC pastors knew about abuse and did not report it. Because pastors do not report abuse, it allows abusers to keep on preying on vulnerable individuals,” Nye told Religion News Service. “Most sexual abusers have multiple victims, which is why it’s so important to report.”

New York state law currently requires doctors, dentists, teachers, day care workers, police officers and several other professionals to report if they suspect a child is abused. Mandated reporters who fail in their duty are guilty of a misdemeanor and are “civilly liable for the damages proximately caused by such failure,” the state law says. Twenty-eight other states already include clergy on their list of mandated reporters, according to 2019 data from the United States Children’s Bureau. Most of these states also include exemptions for clergy who learn about suspected abuse via “pastoral communications,” such as in the context of confession.

Assembly member Monica P. Wallace, who authored the bill and is sponsoring it in the Assembly, told RNS that the CARE Act was designed to prevent leaders from shirking their responsibility to act when they encounter evidence of possible child abuse.

In 2019, New York state passed the Child Victims Act, which carved out a limited-time window allowing adult survivors of child abuse to bring civil lawsuits against their abusers. Months later, a Roman Catholic diocese in Buffalo, New York, filed for bankruptcy as it was inundated with hundreds of lawsuits.

Wallace said the lawsuits highlight the need for greater protections against child abuse, particularly in religious settings. But while the Child Victims Act was retroactive, she said, the CARE Act would be forward-looking.

“What this legislation seeks to do is to fill the void for future situations so something like that would never happen again,” said Wallace, who called the absence of clergy on New York’s list of mandatory reporters a “glaring omission.”