(RNS) — In the 1890s, a pair of British archaeologists began digging in an ancient rubbish heap at the edge of the ruins of Oxyrhynchus, Egypt, looking for a glimpse into the city’s past.

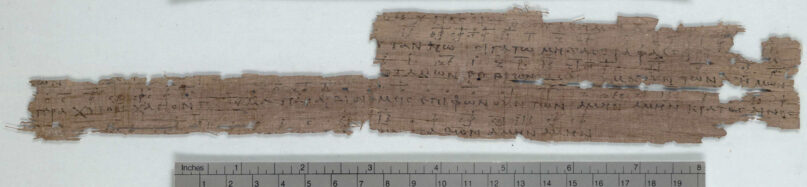

They’d eventually find tens of thousands of documents, written on papyrus and preserved in the desert for centuries, ranging from official documents to personal letters. Among them was a fragment about 11 inches long and 2 inches wide that detailed shipments of grain on one side.

On the other side were the music and lyrics to a song. That song would turn out to be one of the oldest Christian hymns ever found.

RELATED: Chris Tomlin Shares How God Connected Him to ‘The Last Supper’

“We have about 50 examples of musical compositions with musical notation from antiquity,” said John Dickson, a former songwriter turned biblical scholar. “This is the only Christian one. And it predates any other notation of a Christian hymn by many centuries.”

Scholars have known about the fragment, known as P.Oxy. 1786 or the Oxyrhynchus Hymn — a reference to the Oxyrhynchus Papyri collection — since 1922, when the text of the hymn was first published in English. The song is filled with Christian imagery, with worshippers telling the stars and wind to be silent as they praise God, “the giver of all good things,” but the tune is hard to sing. It’s not the kind of song to turn up in a megachurch worship service.

Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 1786. (Image courtesy of Wikimedia/Creative Commons)

The late Martin Marty, a famed Christian historian, once wrote: “If you complain that it’s a bit bumpy and hard to sing, or that it’s ‘one of those old hymns’ and not catchy like the ones that show up on screens, you are right.”

But Marty, who was wrong about few things, might have spoken too soon. A new version of the Oxyrhynchus Hymn debuted last week, courtesy of a new translation from Dickson and help from Chris Tomlin and Ben Fielding, two of the most popular modern worship songwriters.

Christened as “The First Hymn,” the new song arrived just in time for Holy Week, along with a documentary about the hymn that debuts this week at Biola University in Los Angeles and at the Museum of the Bible in Washington, D.C.

Dickson said there are earlier Christian hymns — including several in the text of the New Testament — but none of them has the musical notation found in the P.Oxy. 1786. He said scholars can still read that notation, which comes from an ancient Greek style of music, and so they know what the hymn would have sounded like. The documentary features Dickson singing a bit of the original melody in the ruins of an ancient cathedral.

“I think the most theologically significant thing is that it’s a hymn to the Trinity — Father, Son and Holy Spirit, the century before the Nicene Creed,” he said.

A former songwriter and musician who now teaches biblical studies and public Christianity at Wheaton College in the Chicago suburbs, Dickson said he’s long dreamt of hearing this ancient hymn sung by modern worshippers. But there were a few challenges. One was that the hymn’s original melody would likely not work for a modern audience. The other was that some of the words of the hymn were missing in the fragment.

So he wrote a new translation of the lyrics that remain and gave them to the two songwriters to work with. They used all of his translation and added a more modern melody.

John Dickson in “The First Hymn” documentary. (Video screen grab)

A studio recording of the song begins with an Egyptian vocalist singing along with a guitar part that echoes the original melody of the hymn, followed by a new melody from Tomlin and Fielding. There is also a live version of the song recorded at a stadium-style concert and one sung with a choir.

“All powers cry out in answer,” the new lyrics read. “All glory and praise forever to our God, the Father, Son, and Spirit, we sing amen.”