Members of that youth group formed Willow’s core at its founding, selling tomato plants door to door to raise money for the startup church. At each door that opened to them, Hybels and other leaders would ask the house’s occupant if they went to church.

FILE – The Rev. Bill Hybels, senior pastor of Willow Creek Community Church in South Barrington, Ill., speaks on Jan. 26, 2012. (Photo by Marc Gilgen/Creative Commons)

Beach missed the first service — held Oct. 12, 1975 — but arrived at the church soon after. She didn’t stay long. Those early days were difficult, with too many young leaders, too many new converts and little structure or accountability to keep people in line.

“We were just making it up as we went along,” Beach said in an interview.

“I sensed God saying, ‘Trust me, it doesn’t have to be what you think,” she said, “and I have a big adventure for you.’”

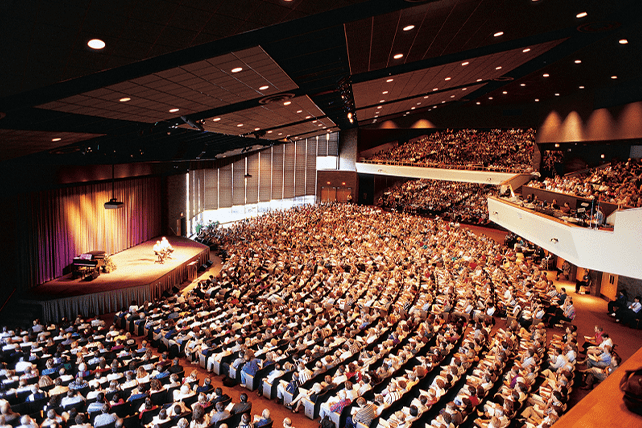

Willow Creek had continued to grow, building its own church on its new 90-acre campus in South Barrington, Illinois, northwest of Chicago in 1981.

The church got its big break when the Harvard Business Review began to pay attention to what the church was doing at the end of the decade. In 1989, management guru Peter Drucker mentioned the church, along with the Girl Scouts and Salvation Army, in an article about what businesses could learn from mission-driven nonprofits.

FILE – Signage for the future main campus of Willow Creek Community Church in South Barrington, Ill., prior to 1980. (Photo courtesy of Willow Creek Community Church)

A few years later, Santiago “Jimmy” Mellado, then a grad student at Harvard’s business school, wrote a case study in the Harvard Business Review that gained national attention. The study told Willow’s origin story, how before founding the church, Hybels and other leaders had asked people what kept them away from church. They found that people were turned off by boring services, irrelevant sermons and churches asking for money with no proof that the money was doing any good.

“The pastor made people feel guilty and ignorant, and so they leave church feeling worse than when they entered the doors,” Mellado wrote, summarizing some of the claims of Willow’s founders. “They attributed their success to the simple concept of knowing your customer and meeting their needs.”

After writing his case study, Mellado worked for Willow Creek for two decades before becoming the CEO of Compassion International, an evangelical humanitarian group. In a recent interview, he said the seeker-friendly focus was only part of Willow’s success. The church gave new converts and established members alike a seven-step process that showed them how to grow their faith and make a difference in the world through active ministry. A key part of that process was the Wednesday night “New Community” service, designed to help members grow in their faith.

Willow stretched “both sides of the spiritual spectrum,” Mellado said. “There was this value, all people matter to God, therefore they ought to matter to us.”

That value — and the way the church focused on helping people grow in their faith — can get lost amid Willow’s decline. Neither the seeker-friendly outreach of the church or its other ministries could have happened without a core group of believers who were devoted to sharing their faith with others — and who put their time and money to work for that cause.

For years, Mellado ran what was known as the Willow Creek Association, a network of churches that shared Willow’s methods. He said the work was not for the sake of insiders like him, but to put people to work making the world a better place for others. He said that at its best, Willow wanted to be a good church, doing God’s work.

“Let’s just be the church that God’s calling us to be,” he said. “And I think all the rest of the stuff will take care of itself.”

The story of Willow Creek’s rise must be told against the background of nondenominational Christianity’s phenomenal growth in the United States over the past half-century. In 1975, established Christian denominations — the United Methodist Church, the Roman Catholic Church, Presbyterian Church, the Southern Baptist Convention and others — ruled the religious landscape. Today, denominations are running on fumes, said Ryan Burge, professor of practice at Washington University in St. Louis who studies the changing religious landscape; nondenominational churches rule the day.