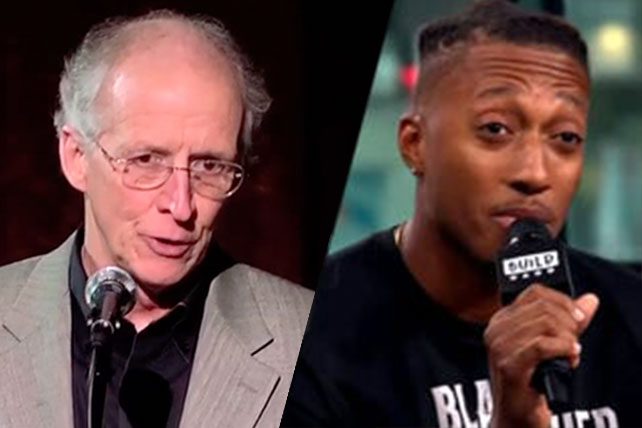

From Ed Stetzer (on whose blog this article originally appeared): At Wheaton College, I have the privilege of serving with a wide array of evangelical thinkers and leaders. One of them is Ray Chang, who serves as Ministry Associate for Discipleship in the Chaplain’s Office. Ray and I recently discussed a letter that John Piper wrote, published in Christianity Today, “My Hopeful Response to Lecrae Pulling Away from ‘White Evangelicalism.’” The Federalist gives a bit of the background.

Over the years, I’ve communicated with both John and Lecrae and, in an odd coincidence, I threw out a shout out at John’s Desiring God National Conference in 2012, about Lecrae teaching us about contextualization. (You can download the book from that talk here.) I am thankful for this conversation about race, and thankful for both men, but also hopeful that we can continue the learning, this time discussing not contextualization, but race and justice.

In order to extend that conversation, here is a letter from Ray Chang to John Piper.

Dear John Piper,

In your Desiring God article, you wrote how you didn’t know what Lecrae’s “loosening from ‘white evangelicalism’ means for multi-ethnic relations.” I’d like to attempt to address this.

Before I do, I’d like to offer up a definition of terms.

Evangelicalism and White Evangelicalism

Evangelicalism: 1) a movement of gospel centrality, focused on the primacy of scripture and justification by faith that emerged from the reformation, 2) a modern movement within Protestantism marked by Bebbington’s quadrilateral of Biblicism, Crucicentrism, Conversionism, and Activism

White Evangelicalism: a segment of modern evangelicalism that is led and shaped by a cultural agenda defined by whiteness.

The reason people struggle to distinguish between evangelicalism and white evangelicalism is because evangelicalism was historically and consistently shaped by whiteness. It was because of this dominance and exclusion within evangelicalism that non-white populations formed their own evangelical organizations (National Black Evangelical Association, National Hispanic Christian Leadership Conference, etc.). Essentially, blacks and Latinos found that their issues and needs weren’t being addressed by their white counterparts, so they started their own movements. It was because white evangelicals didn’t make room for non-white evangelicals that black evangelicalism and Latino American evangelicalism emerged. If they had, we wouldn’t have the need for adjectives before the term evangelical.

I fear that unless white evangelicalism changes in significant fashion, Lecrae is only going to be the beginning of the exodus, despite not being the first to depart.

A couple decades ago, Asian Americans witnessed something Helen Lee called the “Silent Exodus” where the American raised children of immigrant families left the immigrant church for white, second generation Asian American, or multi-ethnic churches. Most left for white churches (or left the church all together) because there weren’t many second generation or multi-ethnic churches to go to.

One of the primary reasons they left was because they felt as though they weren’t considered in the shaping of the church. Instead, they felt like they were put in a siloed enclave that felt more like a guesthouse instead of an integral part of the main home. Though the children of immigrants kept asking for their cultural realities (as people raised in the U.S.) to be represented from the top down, there was a collective unwillingness to let go of the way things have always been from their parents’ generation. In some ways, this was a larger scale occurrence of the worship wars between contemporary and traditional music styles we saw throughout many white churches in America.