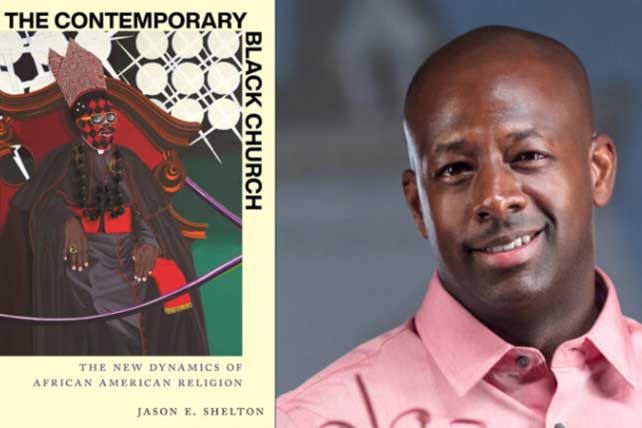

(RNS) — Jason Shelton has made a deep scholarly dive into the world of the Black church.

But not everything in his new book, “The Contemporary Black Church: The New Dynamics of African American Religion,” was learned at the University of Texas at Arlington, where Shelton is a sociologist. He drew as well from his experience growing up in Black churches, in his familial home in Ohio and in Los Angeles — at United Methodist, Church of God in Christ, African Methodist Episcopal and nondenominational churches — and searching as an adult for the right spiritual space for his family.

“It was important to me to find a thriving Black Methodist congregation that I could raise my daughters in, and my wife and I had a difficult time,” he said in a recent interview.

RELATED: After Debate, Black Churchgoers Often Support but Begin To Question Biden

“Here we are in (the Dallas-Fort Worth area), and it’s hard to find a young congregation that’s thriving, where I feel like my daughters can develop their own memories and find bonds with other kids, and we can be with other young families. And so that really made me realize there’s a story here to be told about religion in Black America.”

Shelton, 48, and a colleague developed what he calls “Black RelTrad,” a coding scheme that allowed him to delve into the beliefs and practices of a range of Black believers, including Protestants, Catholics and non-Christians, and nonbelievers.

Shelton, who also is the director of UTA’s Center for African American Studies, talked with RNS about religious differences in Black America, the effects of “disestablishment” on Black churches and whether the “spiritual but not religious” can be reclaimed by them.

The interview was edited for length and clarity.

You open your book recalling your connections with churches from different expressions of the Black church and leaders such as the Rev. James Lawson and Bishop Charles Blake. How did that experience shape you?

Those early years were definitely formative, in that they left me with impressions about various ways that African Americans express faith. When I got to Ohio, I was able to compare St. James (AME Church in Cleveland) to Holman United Methodist Church, and then compare them to the nondenominational church that my parents were attending in Cleveland, and then compare that to West Angeles (Church of God in Christ).

They all left these distinct impressions about variation and diversity. Decades later, I would look back and say, oh my gosh, modern-day researchers have clearly lumped Black folks together like we’re this monolithic group, and I just knew in my own walk in life that was not the case.

RELATED: Dozens of Black Churches Receive Total of $4 Million for Historic Preservation

For years, experts such as Eddie Glaude have asked if the Black church is dead. As you look at the numbers, do you agree or disagree?

I wouldn’t say that it is dead, but certain denominations are in a lot of trouble — that Black Methodist tradition I’ve called home is in a lot of trouble. I’d say the Baptists are also a tradition that has to look and see some trouble down the road. On the flip side, I would say the Holiness Pentecostal tradition in Black America has always been small, but it’s held its ground over the decades. The Black Catholic tradition, always been small, but held its ground. So is the Black church dead? It really depends on which traditions we’re talking about.

What do you see as the main difference between the mainline African American Protestants and the evangelical African American Protestants?

These are Black folks who are believers, and on a Sunday, how they think about, practice their faith, oftentimes are still very similar in orientation. That being said, (some) Black Methodists seem to be a lot more open on LGBT issues, whereas we know the AME (African Methodist Episcopal) tradition is very clear, uh-uh, that’s not a line clergy are ready to cross.

The four traditions in today’s world that comprise the heart of the contemporary Black church are the Baptists, the Methodists, the Holiness Pentecostals and the nondenoms. Of the four of those, the nondenoms are more likely to vote for a Republican presidential candidate. That’s a big break from what we’ve seen in the past.

You describe the “Third Disestablishment in Black America.” What does it mean for the Black church?

You’re seeing these young people, particularly millennials, moving away from organized religion in very strong numbers. The baby boomers held on. It started with my generation in the late 1990s, those Gen Xers. But now with the millennials, it’s moving and taking big jumps forward in terms of the number of African Americans who are not affiliating with organized religion.

You mention the changing levels of education of the Black clergyperson and the Black churchgoers. What’s happened there? What’s at stake?

The idea was that the Black preacher was the leader of the community for most of Black history. In light of all that racism and segregation, the pastor was typically the most educated person in the community because that person could stand up and read the Bible and interpret the Bible and speak to the masses in that congregation. Fast-forward the clock: African Americans in church are oftentimes more educated than the senior pastor in the pulpit. In this modern, technological, mainstream American society, you can sit in church and question what the pastor’s saying in real time.

I argue that a consequence of the success of the Civil Rights Movement is that the church has become voluntary. There was the time that we were expected to be at church. Of course, it’s holding in particular families, don’t get me wrong. But overall, as more and more Black folks have made it to the middle class, and as more and more of us have more options on Sundays, it has undermined organized religion in Black America, and education is the driving force.