WASHINGTON (RNS) — There is no shortage of impressive buildings dotting Capitol Hill: the U.S. Capitol with its shining dome, the Library of Congress topped by a golden flame, the U.S. Supreme Court and its towering pillars.

But on the northeast corner of the Capitol complex is an unassuming building sandwiched between the Supreme Court and U.S. Senate offices. Visitors who notice it at all usually do so because of its church sign, which often features a word or phrase that is surprisingly relevant to the political news cycle.

The sign belongs to the United Methodist Building, the only nongovernmental building on Capitol Hill and one imbued with a rich history of religion, politics and activism. Something of a monument to mainline Christian, ecumenical and interfaith influence in Washington, the building has stood for 100 years, an anniversary celebrated Thursday (Sept. 26) with a special event featuring Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Jericho Brown.

RELATED: United Methodists Elect a Third Openly Gay, Married Bishop

John Hill, then-interim general secretary of the United Methodist Church’s General Board of Church and Society, reflected in May on the significance of the structure and its location. “Every day, when I walk into our offices at the United Methodist Building in Washington, D.C.,” he said during a presentation at the UMC’s General Conference, “I am awestruck by the wisdom of our Methodist forebears who boldly positioned this sacred place directly across from the U.S. Capitol, this place set apart for work, worship and witness to the redeeming power and promise of the gospel of Jesus Christ.”

That work and witness have often involved activism. According to the Rev. Bonnie McCubbin, director of museums and pilgrimage for the Baltimore-Washington Conference of the UMC, the building has had an advocacy-minded edge since it was first conceived in the 1920s. It was originally a project of the Board of Temperance, Prohibition and Public Morals, which emerged out of a Methodist women’s organization that campaigned in support of prohibition, because, according to McCubbin, they “were tired of seeing their brothers and uncles and sons and husbands coming home drunk.” They also opposed lynching, child labor and illiteracy, among other causes.

The Rev. Bonnie McCubbin. (Courtesy photo)

The building’s penchant for ecumenism was also there from the start. McCubbin said the building, constructed with Indiana limestone in an Italian Renaissance style, was dedicated in 1923 by former Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, who had been a candidate for moderator of the Presbyterian General Assembly that year and served on the temperance board of the Federal Council of Churches — the precursor to the National Council of Churches.

But McCubbin, who also works as an archivist for the conference, noted the building was arguably an act of protest in and of itself, as it was “entirely funded by women.”

“Women who didn’t yet have a right to vote, women who didn’t yet have the ability to have their own bank account, women who were not allowed to manage their own house or their own life,” McCubbin said. “In some parts of this country at that time, women were considered property or the equivalent of a child. They were not allowed to make independent decisions without their husband or their father approving it, and yet, in that time, they raised the entire sum of money to build that building.”

The building’s focus began to shift in the 1930s, when Prohibition was repealed by the ratification of the 21st Amendment and the Methodist church reunified in 1939, merging the Methodist Episcopal Church, the Methodist Episcopal Church, South and the Methodist Protestant Church into The Methodist Church. The changes altered the goals of the Board of Temperance, Prohibition and Public Morals, which occupied the building, over time: After the first merger, its name was shortened to The Board of Temperance, and its goal was reset to focus on “creating a Christian public sentiment and in crystallizing opposition to all public violations of the moral law.”

It changed again in 1960, fusing with other boards to become the “Board of Christian Social Concerns,” and later — after yet another major merger in 1968 that resulted in the creation of the United Methodist Church — it was renamed the General Board of Church and Society and tasked with “implement(ing) the social creed.”

Amid all that change, the building’s prominent position on the Hill made it a constant witness to historical events, some of them with Methodists front and center. In 1954, Bishop G. Bromley Oxnam, then-resident bishop of what was called the Washington Episcopal Area, waited in the Methodist Building before he walked over to be interviewed by the infamous House Un-American Activities Committee, the body charged with investigating allegedly disloyal citizens and long associated with anti-communist McCarthyism. (The interview stemmed from false allegations made against Oxnam during his unsuccessful campaign to serve on the Los Angeles Board of Education.)

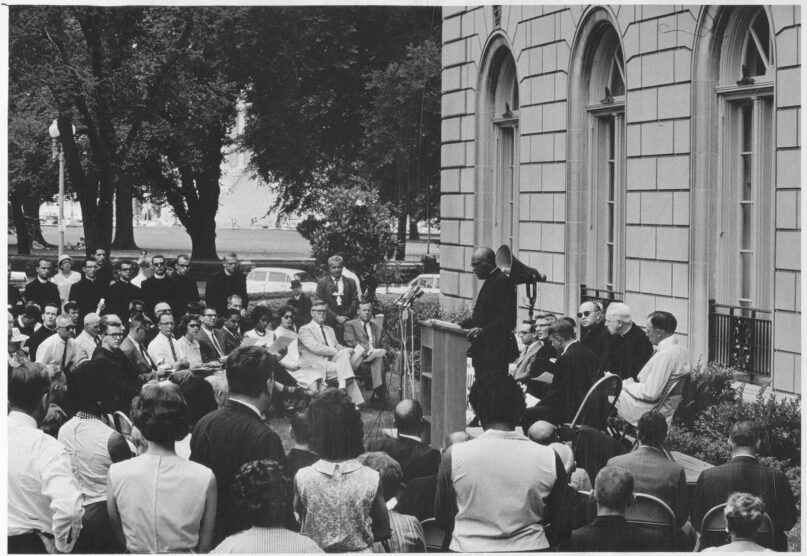

Some 200 Protestants, Roman Catholics and Jews joined in an interreligious thanksgiving service to mark the Senate passage of the Civil Rights Bill and to pledge continued efforts on behalf of racial justice, circa June 10, 1964. The service was held on the lawn of the United Methodist Building in Washington, about a block from the Capitol. Reading the Scripture is Bishop Henry C. Bunton of the Christian Methodist Episcopal Church. (RNS archive photo by the National Council of Churches. Photo courtesy of the Presbyterian Historical Society.)

In addition, in 1965, Bishop John Wesley Lord — who was deeply involved with the Civil Rights Movement and marched with Martin Luther King Jr. — returned to the Methodist Building to “wait over the implementation of racial justice within the life of the Methodist Church and the ongoing struggle for economic and racial justice in our wider society,” according to McCubbin.

The building also features apartments, some of which have been rented to U.S. senators and representatives who desired close access to the Capitol.

A hub for ecumenical and even interfaith organization and activism over the years, today the United Methodist Building hosts offices for multiple mainline Christian denominations such as the Episcopal Church, the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) and the United Church of Christ. Other groups that office there include Lutheran Services of America, Church World Service and the Islamic Society of North America.

In an interview with RNS, Hill, who has worked in the building for more than two decades, said recent years have seen the building become a launching pad for various kinds of activism.