(RNS) — An 800-year-old puzzle about a set of 13th-century floor tiles has added to historians’ thinking about the relationship of Europeans and Arabs at the time of the Crusades.

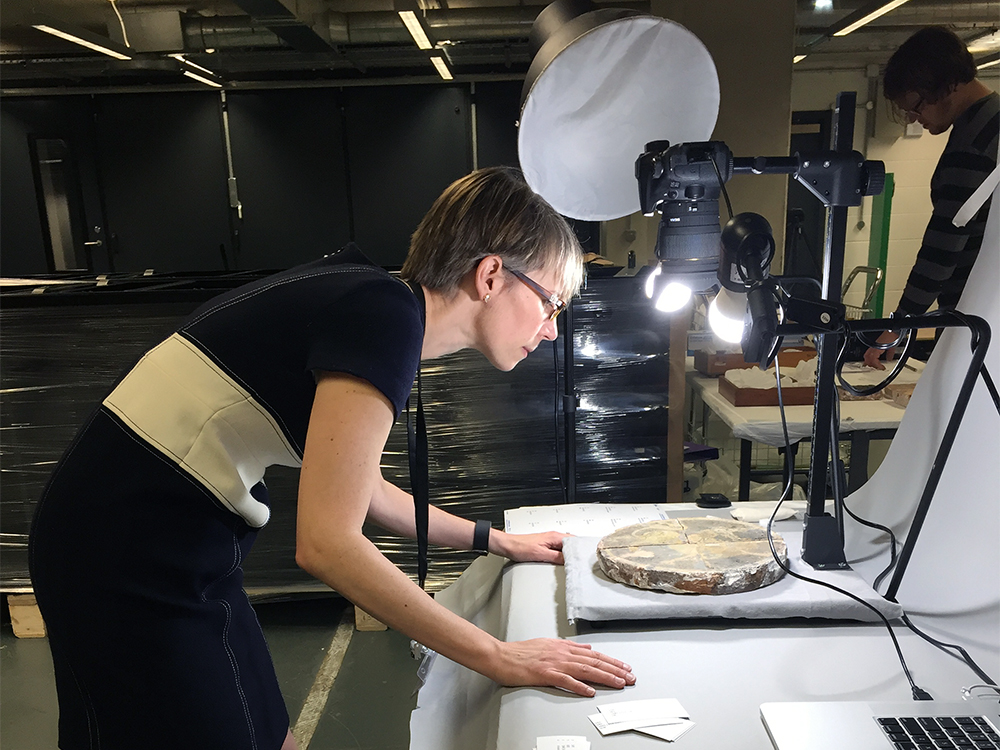

Amanda Luyster, assistant visual arts professor at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, has spent more than two decades studying the so-called combat series, a group of floor tiles uncovered in the 1850s at the ruins of Chertsey Abbey, some 20 miles southwest of London.

Luyster’s research findings underpin the exhibition “Bringing the Holy Land Home: The Crusades, Chertsey Abbey, and the Reconstruction of a Medieval Masterpiece,” which runs Jan. 26 to April 6 at the college’s Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Art Gallery.

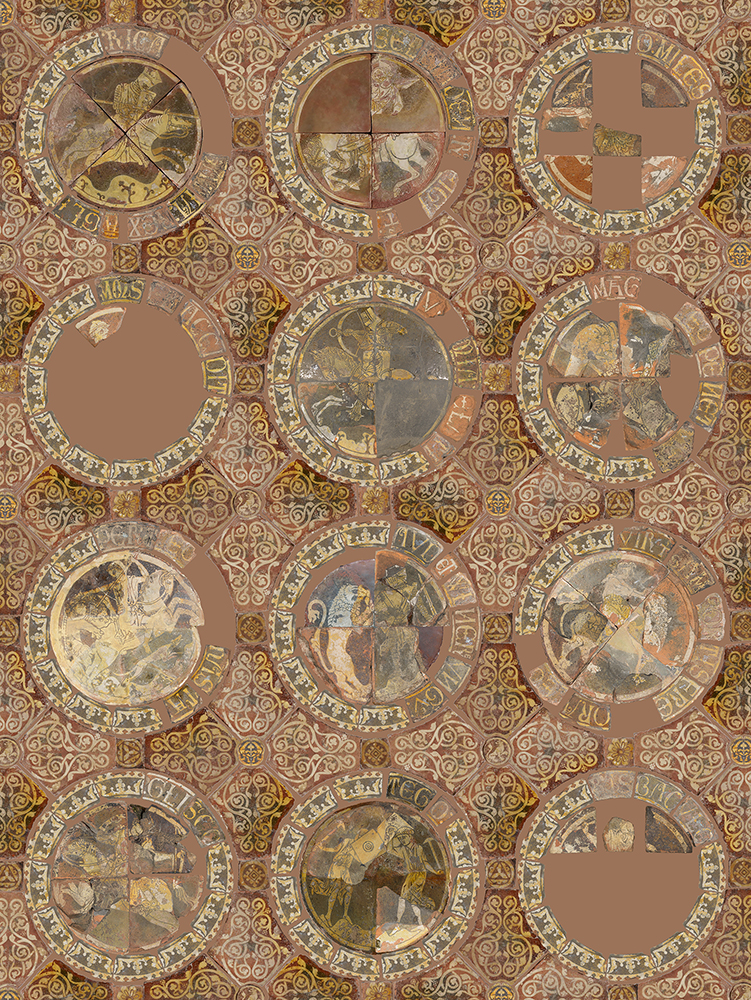

The tiles, which were illustrated and annotated with Latin inscriptions, are among the most significant medieval objects of their kind from England, if not all of Europe, according to Luyster. But since the discovery of the highly fragmented tiles, scholars had largely focused on reconstructing the illustrations, which include scenes of Richard the Lionheart battling Saladin in the Third Crusade a half-century before. The Latin text was too badly broken up at the time to be pieced together and read.

Working with colleagues who coded programs to digitally fit the letters together and cross-referenced them against known Latin texts of the era, Luyster assembled about half of the Latin inscriptions to her satisfaction. She also arranged the illustrations as her research suggests they would have appeared on the abbey floor.

Once restored to their original look, the new design reminded her of Muslim and Byzantine silks that Crusaders brought back as souvenirs.

Digital reconstruction of the Chertsey combat tile mosaic pavement. Photographic composite showing roundels surrounded by partial Latin texts. Photo © Janis Desmarais and Amanda Luyster

Luyster has no illusion that the Crusades, waged from 1095 to 1291, were anything less than major confrontations. But she sees the tiles as telling visual evidence that England during the Middle Ages had robust contact with the rest of the world and that Christian Europe was more porous than historians have believed.

Instead, Luyster said, while the tiles depict Europeans clashing with the Muslims who ruled Jerusalem and the Near East, their manufacture and design reflected familiarity with, and admiration for, Arab artistry. They support the idea that far from thinking of themselves as European, the English who went on Crusades and came back to create these tiles were in deep conversation with Arab culture.

“The Crusaders and other Western Europeans see themselves as Westerners becoming Easterners. Their whole identity is changing, as they move and start living in the area around Jerusalem,” Luyster said.

This cultural fluidity is at odds with a picture of medieval English society as isolated, purely Christian and culturally homogeneous — a view that is increasingly outdated among historians of the period, even as white supremacists in England and the United States have latched onto it.

The key to Luyster’s insight are tiles illustrating the English King Richard I, known as Richard the Lionheart, wounding the Muslim ruler Saladin with a lance, and of a Muslim soldier with an arrow piercing his forehead.

Amanda Luyster at the British Museum photographing the Chertsey tiles in 2017. Courtesy photo

Historians had long known that Richard and Saladin appeared in the overall design of the abbey’s tiles, but other tiles were thought to represent other battles. Luyster’s high-tech detective work on the Latin inscriptions showed, she concluded, that the entire design, not just the Richard and Saladin illustrations, depicted the Third Crusade, led by Richard.