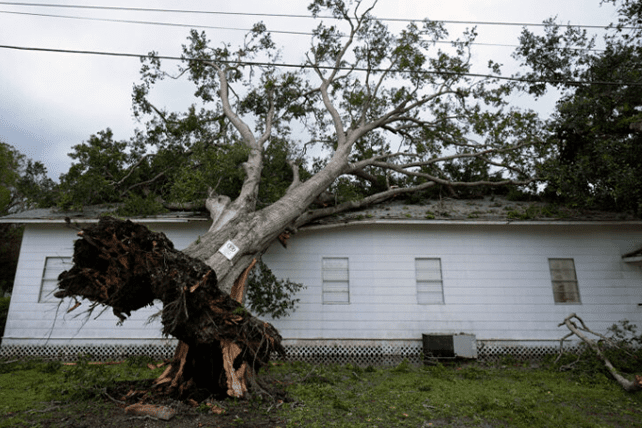

Then a series of natural disasters hit the industry hard — including hurricanes, wildfires and what are known as “severe convective storms” — thunderstorms with extreme rain and wind that caused billions in damage last year, according to the Insurance Journal. Claims from those disasters have stressed the reserves that insurance companies use to pay claims.

AM Best, a credit rating agency that specializes in the insurance industry, cited weather and cost from legal claims as reasons for placing Church Mutual under review this past spring. AM Best also downgraded the rating of Brotherhood Mutual, another major church insurer, while a third church insurer, GuideOne, was taken off review after Bain Capital invested $200 million in the company.

In a statement on its website, Church Mutual said it hopes the company’s outlook will improve.

“Church Mutual has been proactively addressing these challenges to better manage the risks throughout its book of business, nationwide,” the company said. “The company’s leadership team is confident these measures will have a significant, positive impact on profitability in 2024 and beyond.”

Pam Rushing, the chief underwriting officer for Church Mutual, said that the company is still renewing policies and accepting new business in every state. However, the company no longer offers property coverage in Louisiana. Church Mutual did not give details of how many policies have been canceled.

“We do not take nonrenewal decisions lightly and it represents a small percentage of our overall portfolio,” Rushing said in an email. “For us to remain financially strong, viable and best able to serve our mission, we need to mitigate the severe impact catastrophic weather has had – and will continue to have – on our bottom line and our ability to serve customers nationwide.”

Brad Hedberg, executive vice president of The Rockwood Co., a Chicago-based agency, said church insurers are facing pressure from the reinsurers — large companies such as Lloyd’s of London that provide insurance to insurance companies so catastrophic claims don’t overwhelm them. Those companies are looking to reduce their exposure to certain types of claims — meaning church insurers can’t offer as much coverage as they did in the past.

Hedberg, who works with churches and other ministries, said he spends a lot of time helping clients keep the insurance they already have and reduce their risk of filing claims. That means making sure churches have policies in place for everything from abuse prevention to who gets to drive the church van, as well as being proactive with building maintenance and safety projects. It also means being strategic in when to file a claim — and when to pay for a loss out of pocket. Churches should only tap their insurance for large losses — not small claims, he added.

“If small claims get filed, your coverage could be nonrenewed or your premium could go through the roof,” he said. “The market is just that bad.”

Once a church loses coverage, it may face higher prices for years. That’s likely the case for Bethany Covenant Church in Berlin, Connecticut, said Greg Pihl, who chairs the church’s finance committee.

The church had been paying $12,500 for insurance and had made a claim for flooding damage due to a faulty sprinkler. Pihl said the church learned this past spring that its insurance had been canceled. Now Bethany will pay about $73,000 for less coverage, said Pihl.

That made for a difficult conversation at a church business meeting and midyear changes to the church’s budget. The church was able to tap some reserves to cover the increased premium this year. But it’ll likely be paying higher rates for the next three to five years, said Pihl. And those reserves, meant to pay for things like a new roof, still have to be built back up.

Pihl said that before the church’s policy was canceled, he expected rates to go up, perhaps by 10% or 20%. But that proved overly optimistic.

“It’s just a terrible market,” he said.

Nathan Creitz, pastor of Calvary Baptist Church in Bay Shore, New York, a congregation of about 100 people on Long Island, said that in the past, getting insurance hadn’t been a worry. The total annual cost for all the church’s insurance — the church building, a parsonage, liability — was less than $4,000.

“We got lucky,” he said. “We were grandfathered into some really low rates.”

Things changed last summer after Calvary’s insurance carrier dropped the church, deciding not to renew the policy. With the help of a broker, the church found new insurance for about $14,000. Since most of the costs of running a church, such as paying staff and keeping the lights on, are already fixed, that meant cutting programs. The church also had to put off capital improvements to the building, which ironically are the kinds of things that would make them easier to insure.

“It’s not ideal but that’s what happened,” Creitz said.

For Ashford Community Church in Houston, finding the funds to cover the increased insurance has also been a challenge, especially post-COVID, when church attendance and giving are down.