3. Only one state is outpacing its population growth.

Hawaii, where 13.8 percent of the state’s population (1.3 million) regularly attends church, was the only state where church attendance grew faster than its population growth from 2000 to 2004. However, church attendance in Arkansas, Oklahoma, South Carolina and Tennessee—all of which have higher percentages of church attendees than Hawaii—was close to keeping up with population growth in the respective states (see U.S. map on page 50).

In Hawaii, 6.3 percent of the population attended an evangelical church in 2004; mainline denominations accounted for 1.8 percent; and 5.7 percent regularly worshipped in Catholic congregations.

Church Attendance Trends

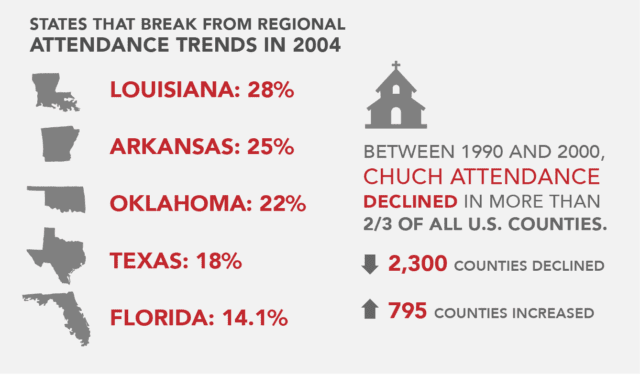

A few states break from regional attendance trends. Texas—in the middle of the Bible Belt and home to more than 17 of the country’s largest churches—saw only 18 percent of its population (22.5 million) attend church on any given weekend in 2004, compared to surrounding states Oklahoma (22 percent), Louisiana (28 percent) and Arkansas (25 percent). And Florida (14.1 percent) had the lowest percentage of the Southern region (averaging 23 percent). Both Texas and Florida saw population growth (2000 to 2004) that was twice the national average.

Olson notes that states with very diverse cultures tend to have lower attendance numbers than the states surrounding them. “Most of our churches know how to address only one culture,” he says.

A closer look at the states only found more decline between 1990 and 2000. Church attendance declined in more than two-thirds of all U.S. counties: Slightly more than 2,300 counties declined, and 795 increased.

4. Mid-sized churches are shrinking; the smallest and largest churches are growing.

While America’s churches as a whole did not keep up with population growth from 1994 to 2004, the country’s smallest (attendance 1–49) and largest churches (2,000-plus) did (see graph on page 52). During that period, the smallest churches grew 16.4 percent; the largest grew 21.5 percent, exceeding the national population growth of 12.2 percent. But mid-sized churches (100–299)—the average size of a Protestant church in America is 124—declined 1 percent. What were the reasons for the decline?

“The best way I can describe it is that a lot of people believe they’re upgrading to first class when they go to a larger church,” Olson says. “It seems highly likely that some of the people in those mid-sized churches are the ones leaving and going to the larger churches.”

Stetzer agrees and adds that because today’s large churches emphasize small groups and community, hoping to create a small-church feel, they offer the best of both worlds.

“There are multiple expectations on mid-sized churches that they can’t meet—programs, dynamic music, quality youth ministries,” he says.

“We’ve created a church consumer culture.”

As president of the Bridgeleader Network, David Anderson, senior pastor and founder of Bridgeway Community Church in Columbia, Md., has consulted with church leaders nationwide. In his work, he has observed that mid-sized congregations tend to lose the evangelistic focus they once had, and instead adopt what he calls a “club mentality.”

“You have just enough people not to be missional anymore,” he explains. “You don’t have to grow anymore to sustain your budget.”

As for why the smallest churches have kept up, Shawn McMullen, author of the newly released Unleashing the Potential of the Smaller Church (Standard), notes that smaller churches cultivate an intimacy not easily found in larger churches. “In an age when human interaction is being supplanted by modern technology, many younger families are looking for a church that offers community, closeness and intergenerational relationships,” he says.

Olson points out that for a church of 50 or less, the only place to go is up. “They have a relatively small downside and a big upside. A church of 25 can’t decline by 24 and still be on the radar. But it can grow by 200.”