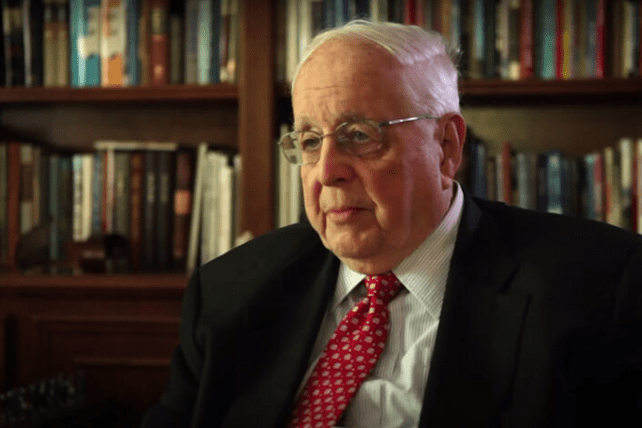

(RNS) — Paul Pressler has long been an eminent Texas Republican, having served as a state representative and judge in Houston. He also once served as the first vice president of the Southern Baptist Convention, but the title doesn’t capture his true place in the firmament of the SBC. As one of the architects of the “conservative resurgence” that reshaped the largest U.S. Protestant denomination beginning in the 1970s, he was been hailed for decades as a hero who helped rid SBC churches of a creeping liberalism.

But recently, Gene Besen, a lawyer for the SBC, called Pressler, 93, a “monster” and “a dangerous predator” who leveraged his “power and false piety” to sexually abuse young men even as he was building his reputation as a conservative reformer.

“The man’s actions are of the devil,” Besen said, clarifying that he spoke in his personal capacity and not as a representative of the denomination. “That is clear.”

What makes Pressler’s case so enraging to many Southern Baptists, however, is that his abuse has been detailed for years. A lawsuit, filed by a former Pressler assistant named Gareld Duane Rollins Jr. claiming the older man abused him for decades, has been making its way through the courts since 2017. (The suit, which named Pressler, the SBC, and other Baptist entities, was settled in December.)

In 2004, the year Pressler was first elected vice president, his home church warned in a letter about his habit of naked hot-tubbing with young men after a college student complained that Pressler had allegedly groped him, according to the Texas Tribune. That same year, Pressler agreed to pay $450,000 to settle Rollins’ earlier claim that Pressler had assaulted him in a hotel room. When Pressler stopped making the agreed payments, Rollins sued again, this time alleging sexual abuse.

Pressler’s downfall also symbolizes a wider failure to deal with sex abuse in the SBC.

In recent years, leaks from the denomination’s headquarters in Nashville and legal filings have shown leaders stonewalling survivors and attempting to force the denomination to face the scope of abuse happening in member churches. The thousands of local church representatives, known as messengers, who make up the SBC’s governing body, meeting once a year at an annual meeting, have voted for measures to identify abusers and keep them from being employed as pastors.

They did so after learning the SBC’s Executive Committee, which runs the organization day to day, had long acted to shield the SBC — and particularly its assets — from liability, a strategy that led the leaders and their attorneys to defend things that were “indefensible,” said Marshall Blalock, a South Carolina pastor and former chair of a task force appointed to address the scandal.

The leaders in Nashville have relied in part on the decentralized structure of the SBC, which they have repeatedly claimed makes reforms impossible to implement. The 47,000 churches of the denomination are independent entities held together by a statement of their beliefs — the Baptist Faith and Message — and their contributions to the Cooperative Fund, established in the 1920s.

The SBC’s more than 13 million members donate nearly $10 billion dollars annually to their churches, nearly half a billion of which goes each year to fund cooperative ministries in the United States and abroad, including six major seminaries and a world missionary force.

While the SBC has no top-down authority, its churches and ministries are deeply interwoven, tied together by a network of state conventions, local associations and “weak ties”— friendships between pastors, leaders and lay people. Its institutions are overseen by volunteer trustees and a handful of staffers in the national office.